10 - Environmental Harm

Contributor – Julia Pitts

Last Updated – March 2009

[10.1] Introduction

Any given morning at around 5am the noise from the back of the commercial premises and lane way can be heard loudly from your new apartment. What can be done to stop this deafening racket? Is this noise at this time in the morning, or at any time of the day, beyond an acceptable level? Is this noise causing environmental harm?

The integrated framework for protecting the ACT environment from pollution and other forms of environmental harm is comprised of the Environment Protection Act 1997 (ACT), the Environment Protection Regulation 1997 and the accompanying Environment Protection Policies (EPPs).

This chapter looks firstly at a few preliminaries such as the objectives of the Act and some of its key definitions. It then looks at the role of the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and the policies and instruments used to prevent and control harm. Finally it looks at enforcement and compliance issues. It should be noted that since the 2003 edition of this handbook The Magistrates Court (Environment Protection Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005 has been introduced and this allows for on the spot fines for a range of offences under both the Environment Protection Act and Regulation.

[10.2] Environment Protection Act 1997

[10.2.1] Objects of the Act

The objects of the Act (s.2) are extensive, contained in sub clauses (a) to (p). They include:

· to protect and enhance the quality of the environment

· to prevent environmental degradation and adverse risks to human health and the health of ecosystems by promoting pollution prevention, clean production technology, reuse and recycling of materials and waste minimisation programs

· to achieve effective integration of environmental economic and social consideration in decision making processes

· to promote the concept of shared responsibility for the environment through public education and the public involvement in decisions about protection, restoration and enhancement of the environment.

· to promote the principles of ecologically sustainable development (and as such requiring decision making to incorporate ecologically sustainable development principles—this is the author's interpretation in italics)

· establishing a single and integrated regulatory framework for environmental protection

· encourage responsibility by the whole community for the environment—general environmental duty

For the purposes of s.2(1)(g) ecologically sustainable development is to be taken to require the effective integration of economic and environmental considerations in decision making processes and to be achievable through implementation of the following principles:

· precautionary principle, namely that if there is a threat of serous or irreversible environmental damage, a lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation

· inter-generational principle, namely that the present generation should ensure that the health diversity and productivity of the environment is maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations

· conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity

· improved valuation and pricing of environmental resources.

[10.2.2] Definitions

The definition of 'environment' is central to the effectiveness of these objects and of the Act. It is defined, along with other terms, in the Dictionary at the end of the Act. There are five parts to the definition, (a) to (g), covering soil, water, atmosphere, organic and inorganic matter, any living organism, human-made structures, ecosystems including people and communities, qualities that contribute to ecological integrity, scientific value and amenity, and the interactions and interdependencies within and between the things mentioned in (a) to (e). In addition it should be noted that (g) is very broad indeed, being ' the social, aesthetic, cultural and economic conditions that affect or are affected by the things mentioned in (a) to (e)'.

The Act deals with gradations of environmental harm, ranging from basic harm, through 'material' to 'serious', depending on its effect over time, its frequency, its cumulative effect, where it happened and the monetary value of the loss or damage caused or of the cost of remedial work. More detailed definitions are incorporated in the 'Offences and penalties' section below.

[10.2.3] How the Act works

The Act protects the environment from pollution and other harms, not by category (for example, as air or water or noise pollution, however there are specific offences under the regulation dealing with water pollution and noise pollution) but rather by a hierarchy of tools, the choice of which depends on the seriousness of the problem and on whether the harm is potential or material environmental harm or serious environmental harm. The Act controls potential and actual harms through environmental authorisations, environmental protection agreements, accredited codes of practice, environmental audits, environmental improvement plans, environment protection orders and, as a last resort, prosecutions.

The Act also implements obligations under the Inter-Governmental Agreement on the Environment (IGAE), which includes the principle of ecologically sustainable development. In decision making the Authority is required to look at the objects of the Act and in particular the precautionary principle and the concept of intergenerational and intra generational equity. It is expected that the decisions made by the Authority should reflect this in their documentation.

At the time of writing the Minister for the Environment, Climate Change and Water was responsible for the Act.

[10.2.4] What is environmental harm?

The primary aim of the Environment Protection Act is to protect the environment from environmental harm. Environmental harm is defined in the Dictionary to mean any impact on the environment as a result of human activity that has the effect of degrading the environment, whether temporarily or permanently.

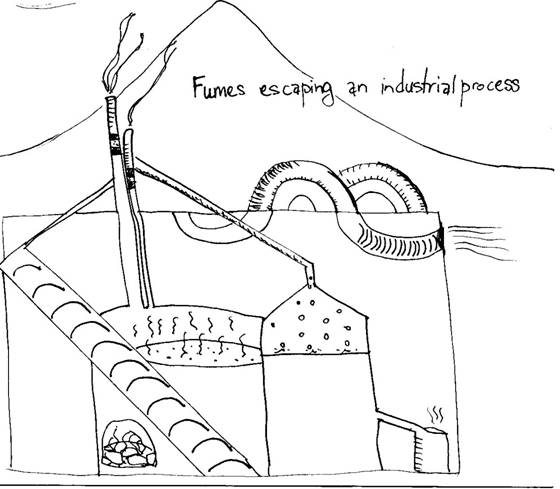

Pollute includes 'to cause or fail to prevent the discharge, emission, depositing, disturbance or escape of a pollutant' and includes the following:

· a gas, liquid or solid

· dust, fumes, odour or smoke

· an organism, whether dead or alive, including a virus or a prion

· energy, including heat, noise, radioactivity, light, or other electromagnetic radiation

· anything prescribed or any combination of the above elements.

The Environment Protection Regulation contains provisions on many of the polluting agents: air (Part 2), noise (Part 3) and water (Part 4). Specific noise zones, standards and conditions are covered in Schedule 2, whilst pollutants prescribed as taken to cause environmental harm on entering waterways are listed in Schedule 3.

Another important clause is s.5 which deals with things taken to have the impact of causing environmental harm, a deeming provision, which means that a thing mentioned in the dictionary definition of pollutant, paragraphs (a) to (e), is taken to cause environmental harm if either the measure of the pollutant entering the environment exceeds the prescribed measure, or it is a prescribed pollutant.

[10.2.5] The Environment Protection Authority

The Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is a statutory position held by the Director of Environment Protection and Heritage, within the Department of Environment, Climate Change, Energy and Water (DECCEW), previously known as Environment ACT. (See ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts.)

One of the key functions of the EPA is to administer the Environment Protection Act and any other functions conferred on it by any other legislation (s.12). In administering the Act the EPA is obliged, among other things, to implement the four principles of ecologically sustainable development set out under 'Objects of the Act' above, plus providing for monitoring and reporting of environmental quality on a regular basis in conjunction with the Commissioner for the Environment.

The EPA works in partnership with business and the community. Recently the appointment of an industry liaison officer has led to a more cooperative approach, an example of this is where the applicant is involved in the development of authorisations. The EPA facilitates a proactive co-regulatory approach tailored to specific activities. This can include non-binding environment protection agreements, accredited environmental improvement plans and voluntary environmental audits, which encourage businesses to meet environmental standards in their own way.

[10.2.6] Environment Protection Policies (EPPs)

The Act is supported by EPPs (Part 4). EPPs are administrative and non-legally binding, providing information to both business and the community on how the legislation will be administered and interpreted by the EPA. The Environment Protection Act requires EPPs to be in accordance with relevant best practice (s.24). Currently there are eight specific EPPs and one general covering general administration of the Act. The specifics cover air, noise, water quality, motor sport noise, outdoor concert noise, hazardous materials, wastewater reuse, and contaminated sites. The EPA is currently in the process of reviewing all the EPPs. Since 2007 the general EPP and the water quality EPP have been revised following public consultation. Public comments were also sought on a revised noise EPP which is in the process of being finalised. These are all public documents accessible on TAMS website (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

EPPs are initially issued as drafts. The EPA publishes a notice on the ACT Legislation Register and the Canberra Times, containing a brief description of the policy, information on where copies can be obtained and inviting anyone to make written comments or suggestions within the consultation period of 40 working days (s.25). The draft EPPs are also automatically sent to the Conservation Council ACT Region and to the Canberra Business Council (s.25(5)). Comments received during this period are considered and the EPA may revise the draft EPP in accordance with the suggestions received. Comments received in submissions then often form part of a working draft paper which may identify which comments have been adopted and why. The draft policy will then go to the minister for consent and a notice of this fact will then be published in the ACT Legislation Register and the Canberra Times (ss27 and 28). The EPPs are publicly available at no charge for inspection at the EPA within TAMS Environment and Recreation Network and on the TAMS website (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[10.2.7] General environmental duty

The Environment Protection Act encourages everyone to take responsibility for the environment by imposing a general environmental duty on the whole community, to take all practicable and reasonable steps to prevent or minimise environmental harm or environmental nuisance resulting from their activities (s.22). However, failure to comply with this general environmental duty is not in itself an offence, and does not constitute grounds for action under the legislation. However, compliance with the general duty can be used as a defence in a prosecution for other offences under s.143.

This general environmental duty is the basis for a number of the EPA's fact sheets. These include information on air pollution giving advice on open air fires, indoor fires and spray painting; information on noise, giving advice on noise in residential areas, including excessive noise; information on hazardous chemicals, giving tips on the safe use, handling and storage of household chemicals plus disposal options; and one on water, giving advice on keeping storm water clean when gardening or washing the car. Copies of these fact sheets are available at the EPA and on its website (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

A member of the public can contact the EPA about any environmental problem by calling Canberra Connect. (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts). In the year 2007-08 the EPA responded to 1949 public complaints: 1389 on noise; 177 on water; 174 on air; 105 on solid fuel heaters; 15 on light; 12 on other hazardous materials; two on pesticides; two on trees; two on land contamination; one on waste collection and 70 on other issues.

These complaints may lead to the EPA issuing an infringement notice and an on-the-spot fine (see [10.7] Offences and Penalties for more details).

[10.3] Environmental authorisations

[10.3.1] Types of authorisations

There are certain activities, those that carry the greatest environmental risk, which must not be carried out without a legally binding authorisation (Part 8). These activities are called Class A activities, they are prescribed in Schedule 1 to the Environment Protection Act and are listed at [10.3.2] Activities requiring authorisation. There are three kinds of authorisation, all covering these prescribed activities:

· standard authorisation that can be for an unlimited period but is usually for three years, subject to an annual review

· accredited authorisation in relation to which effect has been given, or is being given, to an environmental improvement initiative aiming for best practice

· special authorisation where the activity is being conducted for the purposes of research and development, including a trial of experimental equipment, granted for a specified period not longer than three years.

Standard authorisations most commonly authorise a named person to conduct the authorised activity in a specified location, subject to conditions set out in an attached schedule. On the other hand, an authorisation can be individually tailored for the activity it authorises, setting out specific conditions for the conduct of the activity. Under the co-regulatory approach, the applicant can assist with the development of these conditions.

From 1 July 1998 to 30 June 2008, 616 authorisations had been issued, 39 of those in the year 2007-08. A fee is payable. Fees vary substantially depending on the activity and the level of pollutants released to the environment. These fees are currently set out in Environment Protection (Fees) Determination 2009 (No 2) (Disallowable instrument DI2009-209), published on the ACT Legislation Register, but fees may change so it is advisable to check the register for the latest fees determination.

Load based licensing was introduced into authorisations as a means of implementing the polluter pays principle. Fees include a component, which is applied as a rate per kilogram of pollutant that the authorisation holder releases into the environment. The system is modelled on that used in New South Wales.

[10.3.2] Activities requiring authorisation

Authorisations are required for Class A activities, that is, those involving the greatest risks. These include, but are not limited to:

· transport of hazardous waste within the territory

· transport of hazardous waste between states and territories

· motor racing events

· commercial use of chemical products, registered under the Commonwealth's Agricultural and Veterinary Chemical Code (AgVet), for pest control or turf management –this would include, for example, aerial spraying of pesticides

· operation of a commercial incinerator

· operation of sewage treatment plants.

The majority of current authorisations cover the use of AgVet chemicals and the manufacture, sale, storage, supply, transport, use, servicing, disposal of, or dealing with an ozone depleting substance. A number of these latter authorisations are issued to car repairers, for the servicing of car air conditioning systems. A number of firewood merchants also have authorisations, covering the sale or supply of firewood under certain conditions and cutting, storing and seasoning in preparation for sale of firewood in the territory. The public can view current authorisations at the EPA or in its annual report available on its website (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[10.3.3] Conditions attached to authorisations

Section 51 of the Environment Protection Act provides for the types of conditions that can be attached to an authorisation to ensure compliance with the Act. Conditions such as... the applicant shall:

· commission an environmental audit on a specified matter and submit a report of the audit to the EPA

· prepare a draft environmental improvement plan and submit it to the EPA for approval

· prepare a draft emergency plan and submit it to the EPA for approval

· provide a financial assurance of a specified kind and amount to the EPA

· give specified information regarding the environmental impact of the activity at any specified time or times during the period of the authorisation to the EPA

· conduct specified environmental monitoring or testing

· comply with a specified provision of an industry standard or code of practice, being a provision that relates to minimising environmental harm

· comply with specified prescribed standards

· not commence the specified activity until the EPA is satisfied of a specified matter.

The decision to grant an environmental authorisation subject to a specified condition can be appealed in the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT) (see [12.8.4] Tribunal review of a decision for information on making such an appeal).

[10.3.4] Public consultation on authorisations

Under s.48 of the Environment Protection Act the EPA is required to place a notice of an application for an authorisation in the ACT Legislation Register and the Canberra Times, inviting submissions on the application within 15 days.

However, the Minister can make a declaration that public consultation is not required for a particular prescribed activity (s.48(6)). This declaration is a disallowable instrument and must be notified, presented and voted upon in the Legislative Assembly. So whilst certain notifications are not fully transparent, it is possible, with some detective work in the Legislative Assembly, to keep abreast of new applications for environmental authorisations.

A notice of the grant of an authorisation or review of an authorisation must be published in the ACT Legislation Register and the Canberra Times (ss.50 and 59).

[10.3.5] Varying an authorisation

Section 60 of the Environment Protection Act covers the variation of environmental authorisations. Such a variation does not have to be notified. Whilst in many cases a variation is usually a minor change, having no real interest or effect to the broader public, a variation could include a change of ownership where the authorisation is transferred with the sale of a business to another person. A variation can also include a change in the type of activity carried out. This change could be a substantial one. Given that such changes are not publicly notified, then the opportunity for individuals to be aware of these variations and to have the ability to challenge them in the ACAT, are less obvious. Groups and individuals working with this legislation in a public interest capacity need to be aware of the instances where notification of variations are not required, so as to avoid losing their appeal rights to the ACAT.

[10.3.6] Breaching an authorisation

The EPA may, by notice in writing, suspend or cancel an environmental authorisation where it has reasonable grounds for believing that the holder, in conducting the authorised activity, has contravened the authorisation or an environment protection order, or a provision of the Act, and that as a result serious or material environmental harm is occurring, or has occurred (s.63).

An authorisation can also be suspended or cancelled on the grounds that the environmental authorisation was granted or varied on the basis of false or misleading information.

[10.4] Environmental protection agreements

Environmental protection agreements (Part 7) are developed between the EPA and people conducting certain, less harmful activities, usually those known as Class B activities listed in Schedule 1 to the Environment Protection Act. These agreements are formal, written documents that have effect for a specific period of time. There is no fee payable for an agreement. Under s.40 an agreement does not relieve a party from any obligation or duty under the Act or any other law. Agreements acknowledge that companies are motivated to ensure their businesses do not harm the environment. They could, for example, agree to adhere to an industry standard or a code of practice.

Since 1 July 1998 to 30 June 2008, 267 environmental protection agreements have been issued, seven for concrete batch mixing, six for wastewater reuse and four for contaminated sites, one each for municipal services, forestry activities and preservation of wood materials, but the vast majority, 247, were issued for land development and construction sites. These are aimed at achieving better site management, preventing run off, etc.

[10.4.1] Public consultation on agreements

These agreements are notified in the ACT legislation register and in the Canberra Times as having been entered into but there is no public input by way of submissions, as is the case with authorisations (s.41). It is worth mentioning here, that the minister may declare that the notification requirements for agreements do not apply if the Minister is satisfied that the implementation of the agreement is not likely to cause any, or any material, environmental harm. Such a declaration is a disallowable instrument scrutinised by the Legislative Assembly and notified in the ACT Legislation Register. To date no such declarations have been made. Members of the public can view protection agreements at the EPA (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[10.4.2] Breaching an agreement

If an environmental protection agreement is breached, the EPA has the capacity to suspend the agreement. The holder will then have to apply for a legally binding environmental authorisation, for which he or she must pay the appropriate fees. However, if a breach of the Act has occurred he or she may be prosecuted.

[10.5] Environmental improvement plans

An environmental improvement plan is a formal plan to rectify problems, minimise environmental impacts and achieve compliance with the Environment Protection Act (Div 9.1). It can be put in place either to prevent harm or to rectify harm. The EPA can require a plan if there is, or is likely to be, serious environmental harm caused by a contravention of the Act or an environment protection order and the EPA considers that an improvement plan will help to rectify the situation. These plans can also be required as part of an environmental authorisation. Equally they can be prepared on a voluntary basis. The plans have to have regard to relevant best practice. The EPA will either approve the draft plan or reject it and require it be resubmitted. A decision to reject an environmental improvement plan is reviewable by the ACAT. From the Act's commencement to 30 June 2008 four improvement plans were implemented. The public can view these plans at the EPA (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[10.6] Environment protection orders

Where the EPA has reasonable grounds for believing that a person has contravened or is contravening an environmental authorisation or a provision of the Environment Protection Act, it may serve an environment protection order on the person. The order may also be served on the occupier of contaminated land. Between the commencement of the Act and 30 June 2008, 39 protection orders were issued.

The order is in writing, and identifies the person on whom the order is served, specifies the provision of the Act or authorisation contravened, the nature of the contravention, plus the day, time and place where it happened. If the order relates to contaminated land, it will specify the nature of the substances in, on or under the land, the grounds the EPA has for believing the land is contaminated, the action that must be taken, stopped or not commenced by the person, and will set out the maximum penalty on conviction for a failure to comply with an order.

Orders can specify particular requirements of things to be done or not done, including:

· stopping or not commencing a specified activity for a period of time or indefinitely

· undertaking particular action to remedy the harm and, if appropriate, taking action to prevent or mitigate further harm

· restoring the environment in a public place or for the public benefit

· not conducting a particular activity except during specified times or subject to specified conditions

· providing information to the EPA on the environmental impact of an activity being conducted.

[10.7] Offences and penalties

Infringement notices for minor environmental offences are now issued under the Magistrate's Court (Environment Protection Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005. Under s 120 of the Magistrates Court Act 1930 and r.12 an authorised officer can serve an infringement notice on a person if the officer has reasonable grounds for believing that a person has committed certain minor environmental offences which are set out in Schedule 1 to the Magistrates Court (Environment Protection Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005. The infringement penalties range from $1100 downwards for offences committed under the Environment Protection Act, for example, the offence under s.44(1), conducting activities other than prescribed activities, has a maximum penalty if prosecuted of 200 penalty units (1PU = $110) and five times that amount if the offence is committed by a company. If an infringement notice is issued for this offence then the penalty would be $1100 for an individual or $5500 for a corporation. If the fine is not paid within 28 days a final infringement notice is issued that adds an administrative charge to the fine. Prosecution for minor environmental offences can only occur if the person has not responded to the second and final notice and a period of 14 days after the date of the notice has expired.

General environmental offences are dealt with in Part 15 of the Act. The main offences are: s.137 causing serious environmental harm; s.138 causing material environmental harm; s.139 causing environmental harm; s.141 causing (an) environmental nuisance; and s.142 placing a pollutant where it could cause harm.

The difference between material and serious environmental harm is a question of degree. Material harm requires that it be 'significant' over time, or due to its frequent recurrence or due to its cumulative effect with other relevant events, or in an area of high conservation value and the harm is not trivial or negligible or loss or damage to property is valued at more than $5000, or remedial action costs more than $5000. Serious environmental harm is the same as material harm except it covers where the harm is 'very significant' or where loss or damage or remedial costs are over $50,000.

Serious environmental harm has a maximum penalty that is twice the amount for material environmental harm. Within each offence there are differing penalties. This is based on whether a person: knowingly or recklessly polluted; negligently polluted; or polluted the environment. The level of penalty therefore depends on both the seriousness of the harm and the offender's state of mind. These relationships are most easily expressed in a table.

|

|

Serious |

Material environmental harm |

Environmental harm |

|

Knowingly or recklessly polluted |

2,000 penalty units, prison for five years or both |

1,000 penalty units, prison for two years or both |

100 penalty units, prison for 6 months or both |

|

Negligently polluted |

1,500 penalty units, prison for three years or both |

750 penalty units, prison for one year or both |

75 penalty units |

|

Polluted |

1,000 penalty units |

500 penalty units |

50 penalty units |

Under s.145 further specific offences relating to the sale of articles that emit excessive noise and fuel burning equipment have been prescribed under Schedule 2 of the Act.

In terms of prosecutions as at the 30 June 2008 only three cases have been prosecuted.

Given that the ACT is mainly a government town it is worth noting s.10 of the Environment Protection Act which deals with the criminal liability of government entities. It says that except as expressly provided by this Act, a government entity is not immune from criminal liability under this Act in relation to an authorised act or omission of the entity. But then s.10(2) offers immunity from prosecution in relation to the key environmental offences under the legislation:

· section 45—compliance with an authorisation

· section137(3)—pollution of the environment causing serious environmental harm

· section 138(3)—pollution of the environment causing material environmental harm

· section 139(3)—pollution of the environment causing environmental harm

· section 141—causing an environmental nuisance

· section 142—placing a pollutant where it could cause harm

· section 142(b)—offending against a regulation that is prescribed for this section.

[10.8] Review in ACAT or Supreme Court

Under s.136B of the Environment Protection Act an eligible person may apply to the AAT for review of a decision of the EPA. An eligible person is a person mentioned in column 4 of schedule 3 to the Act or any other person whose interests are affected by the decision. There is a long list of reviewable decisions set out in schedule 3 to the Act, including: (item 1) exclusion of or refusing to exclude a document or part of a document from public inspection; (item 7) granting an environmental authorisation subject to a specified condition; and (item 11) varying an environmental authorisation. See [12.8.4] Tribunal review of a decision for more information on actions in the ACAT.

In addition to lodging an appeal in the ACAT, persons working to protect the environment for the public interest should be aware of the much under utilised tool of an injunction, available under Division 13.3 of the Act. Where there is a breach, or a likely breach, of an environmental authorisation, an environment protection order, or of the Act that has or is likely to cause serious or material environmental harm, the Supreme Court may order the respondent to remedy the breach, or to stop committing the breach, or where the breach is anticipated, to not commit the anticipated breach (s.128). If the matter is urgent, it is possible to seek an interim order, but the court must be convinced that there is a real or significant likelihood that serious or material damage will occur before the initial application is decided (s.129).

Applications for injunctive orders can be made by the EPA or by any other person. However, the court will only grant leave to any other person to make an application where the person has first asked the EPA to take action and it has failed to do so, and where the proceedings will be in the public interest (s.127). The barriers to making an application in the ACT are much higher than those in NSW where any person can make an application to the Court under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW) s.252 and they only have to establish a relevant breach of that Act.

It should be noted that there are risks associated with seeking such an injunction. The court may ask you to give security for costs, that is, to show that you will be able to pay the costs of the other party if your application fails (s.131). In addition, if you fail, you may have to pay compensation to the person alleged to have breached an authorisation, order, or the Act (s.132).

[10.9] Human Rights Act 2004 and environment related rights.

The EDO argued for a specific environmental right in its submission to the 12 month review of the Human Rights Act. "The Human Rights Act 2004 should provide that everyone has the right to an environment that is not harmful to health or well being, and to have the environment protected for the benefit of present and future generations, through reasonable legislative and other measures, that (i) prevent pollution and ecological degradation (ii) promote conservation and (iii) secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources which promote justifiable development"

This policy position was not adopted as one of the review outcomes.

However recent international cases and jurisprudence suggest that the Human Rights Act can be read to include environment related rights in relation to the right to life, the right to protection of the family and children, the right to privacy and reputation, in such cases as excessive noise for residents near the Summernats motor sports event or high levels of air pollution from stationary traffic at traffic lights or intersections near child care centres or primary schools.

[10.10] Conclusion

The Environment Protection Act 1997 and accompanying regulation offer a range of tools and mechanisms that can implement and enforce best practice environmental law within the ACT. The majority of the recommendations arising out of the statutory review of the Act in 2004 and agreed to by government have now been implemented. See Review of the Environment Protection Act 1997 and the Role of the Environment Protection Authority, Final Report, June 2004.