12 - TAKING ACTION

Contributor – Christal George

Last Updated – March 2009

[12.1] Introduction

We are the people we have been waiting for

- June Jordan, poet

Canberra is a transient base for politicians from the states and territories. Hence it is a meeting place that attracts the largest number of lobbyists, think tanks and bureaucrats in the country. Canberra also has the highest average disposable income of any Australian capital city. The car is by far the dominant form of transport. The town is also characterised by a well worn labyrinth of cycle paths and nature parks. According to the 2006 Census, about 6.3 per cent of the populus walk or cycle to work. Namadgi National Park is located 40 km southwest of Canberra city and makes up approximately 46 per cent of the ACT's land area.

Since the first edition of the ACT Environmental Law Handbook was published in 2002, victories of local groups taking action have included halting the proposed dam in the Naas Valley and the DragwayAway campaign to re-locate a dragway planned for Majura Valley. There has also been ongoing lobbying and law reform work undertaken by environment groups including Pedal Power, Canberra Ornithologists Group, the ACT branch of Australian & New Zealand Solar Energy Society, and the peak organisation that advocates on environmental issues in the ACT, the Conservation Council ACT Region (Conservation Council) (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

Also since the previous edition and prominent in the news were the activities of a coalition of local environment groups who took action against the building of the Gungahlin Drive Extension through sections of Canberra Nature Park (Bruce Ridge, O'Connor Ridge and Black Mountain Nature Reserve). One of these groups, Save the Ridge, challenged decisions of ACT and Federal governments in the ACT Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) and the ACT Supreme Court. However the ACT Legislative Assembly passed a law, the Gungahlin Drive Extension Authorisation Act 2004, to facilitate the construction of the road and limit appeal rights. This Act abruptly ended, in mid-stream, legal challenges concerning breaches of ACT's environmental and planning laws.

In addition to local issues, groups regularly gather in Canberra to take action on national environmental issues, and where they intersect with other issues of significance. The Parliamentary Triangle has been the site of protests relating to the war in Iraq, the visit of US President Bush and Chinese President Hu Jintao, logging in Tasmanian forests and an ongoing site of significance for the Aboriginal rights movement.

[12.2] Scope of Chapter

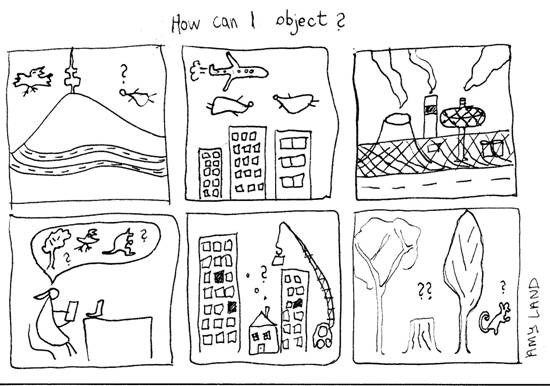

Taking action can be broken down into eight elements:

1. research—background science, economics, key players, policy context

2. disseminating information to public—events, stalls, website

3. media—building relationships, effective messaging, creative stunts, timing

4. legal and parliamentary platforms—FOI, going to court, parliamentary processes, law reform

5. political—supporting candidates, how to vote cards, the running of fair elections, lobbying

6. fundraising—seeking donations, grants, selling merchandise

7. non-violent direct action (NVDA)—necessity, safety, police, media, logistics, criminal justice system

8. personal sustainability and growth/survival of group—trust exercises, active listening, establishing decision making processes.

Think of these eight elements as tools in your toolbox that need to be in working order; the use of a tool or a number of tools involves strategic consideration of the bigger picture. Going to court is just one strategy/tool; very rarely is it the solution in itself. The group must monitor and anticipate the bigger picture, including how your action ties in with public sentiment, the election cycle, the legitimacy of the group's objectives, and the reasonableness of the solutions being proposed.

This Chapter provides information on element 4, the legal and parliamentary platforms, and element 7, criminal law aspects of NVDA. More detailed inquiries on the information here can be directed to the Environmental Defender's Office (EDO) in the ACT (see Contacts list at the end of this book).

[12.3] Finding like-minded people

What makes some people decide to take action on environmental issues? There are different reasons people get together, including the desire to 'make a difference' or to achieve a very specific objective. In Canberra, the level of education is a factor in people taking action because they are often knowledgeable about the issue and why it is important to act. For example, individuals and groups taking action on climate change have reached an all time high, shown by the interest in the Walk against Warming (WaW), organised by environmental groups around the world and in Australia. In 2004 there was no WaW in Canberra, in 2005 the turnout was 300, in 2006 that leapt to 3000 (also the estimated figure for the 2008 turnout), and in 2007, 9000 people showed up.

To start, think about whether another group is working on your issue. Sticking with the climate change example, there are many different angles, so it can work that there are many groups. The main thing is to establish relations with the other groups and communicate. However, if you want to monitor water quality in your catchment you would be better working within a catchment group, or if you have an interest in the way development deals are done in the ACT, contact your local planning associations, any active resident groups and also your local politician. At the very least when taking action ask around and find out what groups are already out there.

The Conservation Council is the 'umbrella' conservation organisation in the region and many groups can be found on its website (see Contacts list at the end of this book). It currently has about 30 member groups which can be viewed on their website. The work of the Conservation Council includes directly lobbying government and agencies on environmental issues in the ACT and region. They also provide education and literature on environmental issues and have established working groups which are open to people to be involved. The working groups focus around each of the Conservation Council campaigns: water, biodiversity, climate change, transport, planning, pollution & waste, and sustainability.

You can also get involved with community groups through 2XX 98.3fm community radio. It has a variety of shows which specialise in local, regional and global environmental issues.

[12.3.1] Incorporation

However, if there is no-one working on your issue then starting your own group is an option and whether to incorporate or not becomes an issue. Incorporation gives the group its own formal separate legal identity; you are no longer a group of individuals. There are some distinct advantages to incorporation, including:

· providing a separate legal entity which can open bank accounts, enter into contracts, take out insurance, hold assets, etc. in its own right

· limiting the financial liability of the group's members in respect of the debts of the group

· establishing clear aims and objectives which are included in the group's constitution/articles of association

· meeting the requirements of some funding bodies that only provide funds to an incorporated entity.

Offsetting these advantages are other factors, such as:

· the costs, both financial and administrative, of creating and maintaining the incorporated entity

· the risks associated with being a director or office bearer of an incorporated entity, risks that are similar to those of being a director of a company.

Additional to these legal considerations, group activities and experience may suit a less formal way of organising, for example an affinity group model or empowerment model.

In the ACT, environmental groups can become an incorporated association under the Associations Incorporation Act 1991 (ACT) (Associations Act). Another, but less common alternative, is to establish a company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The former is a simpler process, resulting in an entity that is less costly to create and maintain, has less ongoing regulatory requirements, and for which the penalties for breaching any regulatory requirement are not as severe. Regardless of the structure, however, it would be prudent to obtain independent legal advice before proceeding.

To become an incorporated association under the Associations Act, you will need:

· at least five members (s.14)

· a constitution/articles of association to set out the group's aims and objectives and rules on how it will function, voting, quorums, timing of the AGM etc (Part 3)

· a public officer to be the legal face of the group and to lodge documents at the Registrar-General's office (s.57)

· an auditor to check the financial affairs of the group (Part 5)

· a committee made up of at least three members to organise the activities and manage the finances of the group (s.60).

The Associations Act and the Associations Incorporation Regulation 1991 set out more detailed requirements on all these points. You can purchase a copy of the Act and Regulation or download a copy from the ACT Legislation Register (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts). The Regulation contains a model set of rules that can be adopted as your constitution/articles of association. Alternatively, if you decide to change the constitution to suit the group's needs, or totally replace it with your own, a checklist of the core rules that must be included in your constitution is available.

The ACT Registrar-General manages incorporated associations and that office can provide information and advice (see Contacts list at the end of this book). If the incorporated entity is to hold a bank account you must apply for a tax file number. If it is a not-for-profit entity, an application is made for income tax exemption. Without either of these your bank will be required to withhold income tax out of any payment of interest. Application forms are available from the Australian Taxation Office (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[12.3.2] Tax deductibility

Being an incorporated entity is also one of the business structures acceptable for tax deductibility under the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Income Tax Act). The Commonwealth Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts administers the Register of Environmental Organisations. Any money paid into the public fund of a registered organisation can be claimed by the person giving the money as a tax deduction.

For a group to be eligible for the register there are a number of criteria that must be satisfied and a number of these criteria must be included in the group's constitution. Under the Income Tax Act (ss.30.265, 30.270, 30.275) in order to be eligible, the group must have been established for the principal purpose of either:

· protection and enhancement of the natural environment or of a significant aspect of the natural environment

or

· provision of information or education, or the carrying on of research, about the environment or a significant aspect of the environment.

Further, the group must:

· have at least 50 individual voting financial members

· be not-for-profit

· establish and maintain a public fund in Australia for gifts of money or property for its environmental purposes that is only used to support the body's environmental purposes and Taxation Ruling 95/27).

For information on eligibility for the register and application guidelines see the department's website (See ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[12.3.3] Define objectives

If you incorporate your constitution must include the group's objectives, but even if you do not incorporate, take time to define your objectives. This will provide a focus for people in the group to work around and can potentially avoid conflict between members at a later stage.

Get it sorted out at the beginning and have processes for introducing new people to the group's objectives and the ground rules, which will include dispute resolution mechanisms. When you are taking on an issue that will require dedication over some period of time, ground rules are an essential to assist with unity. If personality conflicts arise, objective dispute resolution guidelines can be followed and will not detract from the group's focus, which should always be the aims and objectives of the campaign.

The Environmental Defender's Office (NSW) factsheet on incorporating an environmental group sets out further reasons for incorporating. For example, it can help to 'bulletproof' your organisation from take-over, provided you have defined your objectives in specific enough terms. Some organisations have faced take-over bids because they have defined their objects too broadly, for example, 'the protection of the environment'. Framing your objects more specifically allows for more control over the organisation. For instance, 'protecting the environment by working for the creation of national parks'. Those who do not agree with the objectives can be prevented from joining or asked to leave.

In circumstances where it may be necessary to pursue legal rights of redress, a group's aims and objectives as set out in a constitution will be a relevant factor (see [12.8] Lawyers, the ACAT and the Courts for information on taking court action).

[12.4] Access to information

There are many public information sources that may be of assistance when taking action. Clues to corporate decision making can be found by accessing company annual reports and literature. Information regarding government decisions may be sought under the Freedom of Information Act 1989 (ACT).

[12.4.1] Freedom of information

Sometimes the information you require about a decision made by a government department may be available for a fee, or the department or agency may be willing to provide the information if an informal request is made politely; email the department and follow up with a phone call. For other situations, the Freedom of Information Act 1989 (ACT) (FOI Act) provides guaranteed rights to obtain certain kinds of information.

The FOI Act was enacted as an accountability measure supporting a commitment to open government and transparency. The FOI Act creates a legal right for any member of the public to access certain documents held by ACT ministers, government departments and some statutory authorities. It also gives the public access to information about the organisation and operations of departments and agencies, including procedures used in making decisions and their arrangements for public participation. It may also be possible to peruse or purchase copies of manuals, or parts thereof, and guidelines used by government agencies for making decisions.

The types of documents accessible to the public under the FOI Act include procedure manuals, guidelines, files, reports, computer printouts, maps, plans, photographs, tape recordings, films or videotapes.

Whilst the public has right to information, some information is subject to a number of exemptions. These include:

· protection of personal privacy (s.41)

· public safety (s.37)

· law enforcement (police) activities (s.37)

· where disclosure could prejudice the security of the ACT (s.37A)

· where all the work involved in an FOI request involves an unreasonable diversion of resources (s.23).

Each government department has FOI officers to assist with the requests for information. You must identify the document or documents you want to access, for example, by giving the date the document was created or by describing in detail the matter in which you are interested. You then make a request either by writing to the department or by filling in an FOI application form (s.14).

The department or agency must acknowledge receipt of your request within 14 days. Further, the responding agency must notify you of its decision on access within 30 days (although this may be extended by 30 days in certain cases) and give you notice of any charges that are payable (ss.18 and 28). If you are granted access, you will receive a copy of the document or you will have the right to view the document at the department or agency. The document you see may contain sections that have been deleted or blacked out, for example, information about another person may be deleted. If access is refused, you must be given a statement setting out the reasons why access was refused (s.25).

If you are unhappy about a decision that denies access to information or that imposes a charge, you can ask the department within 28 days of being notified of the original decision for an internal review (s.59). You will be notified of the reviewed decision within 14 days and, if access is still denied, you will be given reasons why access has been denied. If still unhappy, you can apply to the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT) for merits review or to the Ombudsman (see [12.8.4] Tribunal review of a decision and [12.6] The Ombudsman).

Application fees for FOI requests were abolished on 22 March 2001. Processing charges may still be levied, for work in excess of 10 hours processing time and/or 200 A4 photocopies (clause 2(3) and item 2 of Part II of the Schedule of the Freedom of Information (Fees and Charges) Determination 1995). Applicants may wish to bear this in mind when formulating their request.

There is a similar process available under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth) for information held by Commonwealth departments and agencies. General information on FOI is available on the Commonwealth Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet's web site (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts). The EDO (ACT) has produced fact sheets on accessing FOI in the ACT and the Commonwealth. (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[12.5] Parliamentary/Assembly processes

The first sitting of the ACT's Legislative Assembly took place on 11 May 1989 in rented premises at No 1 Constitution Avenue, Canberra City. The seventh Assembly, running from 2008-2012, is comprised of 17 elected representatives; the Australian Labor Party holds seven seats, the Liberal Party six seats and the ACT Greens four seats. The ACT Legislative Assembly's website contains up-to-date member and committee information, parliamentary documents, including minutes of proceedings, notice papers and daily programs (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[12.5.1] Assembly committees

Assembly committees are divided into two types, standing committees and select committees. Standing committees are established for the term of each Assembly and there are currently two relevant ones, dealing with environmental issues: the Standing Committee on Planning, Public Works and Territory and Municipal Services and the Standing Committee on Climate Change, Environment and Water. Select committees are created for a specific purpose; one example is the Estimates Committee where committee members examine proposed government expenditure. This provides an opportunity to ask questions of the majority government on the allocation of taxpayer's money.

Committees are made up of members of the government, opposition and independents, usually about three members. Committee inquiries are often instigated because members of the Assembly perceive there is public interest or concern about an issue. In recent times the previous Standing Committee on Planning and Environment held inquiries into the Sustainable transport plan, exposure draft of the Planning and Development Bill 2006, water use and management, and Namadgi National Park draft management plan.

Groups and individuals can contribute to committee inquiries by attending a public forum, lodging a submission, appearing at a hearing. A committee inquiry is usually advertised in the newspaper or on the Legislative Assembly website. Following an inquiry the committee will report to government on its findings and may make recommendations for change.

The government provides a response to the recommendations, usually within three months, outlining what recommendations it has accepted, those it has not, and the reasons why.

[12.5.2] Question time and questions on notice

Questions and questions on notice can be an effective way of obtaining information from government which is not obtainable by other means. Community groups may ask Legislative Assembly members to ask questions of the Government.

[12.5.3] Annual reports and Auditor General reports

Another useful source of information is annual reports of government departments and agencies. Annual reports are produced at the end of each financial year, usually printed in September, and are publicly available.

These must include a report on how the department or agency is pursuing the goal of ecologically sustainable development (ESD) (s.158A Environment Protection Act). There are no targets set for reduction in energy use, water use or waste across all departments. Hence general information is provided on a variety of activities each department has undertaken throughout the reporting year, depending on the level of commitment and the culture of that department.

The Auditor-General is responsible for undertaking audits of management performance and financial statements of government bodies. These reports are one method of ensuring accountability in the executive arm of government.

[12.5.4] Matter of public importance:

Matters of public importance are a topical issue of concern to the community which is suggested for discussion by a member of the Assembly. They can be a useful way of raising an issue.

[12.5.5] Presenting petitions, submission and letter writing:

When writing a letter or a submission be polite, and address the issue in question. Try and be concise and use headings. Submissions may have a prescribed format which you will need to adhere to.

A petition is a written request, calling for the redress of a grievance or seeking action, presented to the Legislative Assembly by a member. The request must be written on every page containing signatures. All petitions must be respectful, accurate and reasonable. The ACT Legislative Assembly website has information on the format of a petition, plus contact details for all MLAs (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[12.6] Ombudsman

The ACT Ombudsman has broad powers under the Ombudsman Act 1989 (ACT) to investigate complaints that relate to matters of administration, including complaints regarding ACT government agencies, ACT policing, how an FOI request was handled, and whistle blower complaints. In some instances, the ACT Ombudsman refers complainants to other review agencies that can more appropriately deal with the issues raised (ss.6A and 6B). These issues may include complaints about the environment.

The Ombudsman has a limited role in the environmental area. Specific responsibility for investigating complaints about the management of the environment in the ACT lies with the Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment. Complaints regarding environmental administration will generally be referred to the Commissioner (see [12.7] Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment).

The ACT Ombudsman does not investigate actions taken by:

· the territory or a territory authority for the management of the environment

· the Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment

· a minister

· a judge or magistrate or tribunal (s.5(2)).

The distinctive feature of the ACT Ombudsman is that its findings are not 'determinative' or final (unlike a court or tribunal). The Ombudsman's powers are recommendatory; he/she investigates and then may recommend that the government department undertake one of the following:

· reconsider or change its decision

· apologise

· change a policy or procedure

· consider paying compensation where appropriate (s.18).

The Ombudsman also has the option of publicly airing his/her recommendation if an unsatisfactory response is received from the government. This can be embarrassing for the government department concerned.

[12.6.1] Making a complaint

The Ombudsman provides a free service. Complaints may be made by going to the Ombudsman's office, by telephone, in writing (by letter, email or facsimile), or by using the online complaint form on the Ombudsman's website (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts). Complaints will be accepted anonymously.

The Ombudsman's website includes tips on making a complaint:

· keep track of conversations with the government agency—ask for a reference number and names

· set out your complaint clearly and briefly—stick to main facts do not go into excessive detail

· if detail is necessary it is useful to set it out in the format of a timeline

· include information about each contact with the agency and what happened with details of who you spoke to, or who wrote to you

· any steps you have taken to sort out the problem

· keep any relevant documents, including all correspondence with the agency.

You can also suggest to the Ombudsman what action you think may be taken to resolve your complaint. Keeping accurate records is also useful when considering pursuing legal action (See [12.8] Lawyers, Tribunals and the Courts).

[12.7] Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment

The position of ACT Commissioner for the Environment was established under the Commissioner for the Environment Act 1993 (ACT), to operate as the ombudsman for environmental matters. This role and title was expanded in 2007 to include sustainability. In that role the Commissioner shall:

· produce State of the Environment reports for the ACT—at the time of writing the most recent SoE Report for the ACT was published in 2008

· investigate complaints from the community regarding the management of the territory's environment by the ACT government or its agencies

· conduct investigations directed by the minister—for example, in 2007 the commissioner was directed by the Minister for the Environment to investigate lowland native grasslands, including their associated threatened communities and species (such as the Grassland Earless Dragon, the Striped Legless Lizard and the Golden Sun Moth), as well as threats to, and identification of measures for protection

· initiate investigations into actions of the ACT government or its agencies, where those actions have a substantial adverse impact on the territory's environment

· make recommendations for consideration by the ACT government, and include in the annual report the outcomes of those recommendations.

[12.7.1] Making a complaint

Section 12 of the Commissioner for the Environment Act sets out what the commissioner can and cannot investigate. Under s.12(2), the commissioner is not authorised to investigate action taken by any of the following:

· a judge or the master of the Supreme Court

· a magistrate or coroner for the ACT

· a royal commission under the Royal Commissions Act 1991 (ACT)

· a board of inquiry under the Inquiries Act 1991 (ACT)

· a panel conducting an inquiry under Chapter 8 of the Planning and Development Act 2007 (ACT), dealing with environmental impact statements and inquiries

· the Ombudsman.

Section 14 details the discretion available to the Commissioner not to investigate certain complaints, similar to the Ombudsman's powers.

[12.8] Lawyers, the ACAT and the Courts

[12.8.1] Finding the right lawyer

When dealing with a legal issue it is important to find a lawyer that specialises in the particular area of law with which you are concerned. For example, EDO specialises in environmental law and is a good starting point for getting assistance in environmental matters. If the EDO cannot assist they can assist in referring the matter to an appropriate lawyer.

[12.8.2] Review within the agency

If you are unhappy with a government or agency's decision the first step is usually to seek reconsideration for a decision (internal review, as discussed earlier). This is done by someone other than the decision maker in the department.

Legislation will set out which decisions are subject to internal review. For example, under the Tree Protection Act 2005 a decision by the Conservator of Flora and Fauna to approve or refuse a tree management plan, or to approve or refuse a tree damaging activity, or to cancel such an approval, may be internally reviewed. In such a case the internal review must reconsider the conservator's original decision having regard to any advice from the advisory panel (s.106, Tree Protection Act).

[12.8.3] Asking for reasons

It is also possible to obtain a written statement of reasons for some government decisions.

It is important to seek a statement of reasons so that you can make an informed decision as to whether to take the matter further, for example by making representations to a Member of Parliament, complaining to an ombudsman, seeking internal review or review by a tribunal, or commencing proceedings in a court.

For certain decisions a government agency will automatically be required to provide a person with a statement of reasons for their decision. For example, if the ACT Planning and Land Authority approves a development application under s.162(1)(a) or (b) of the Planning and Development Act, ACTPLA must provide the applicant and anyone who has put in a submission relating to the development application, a notice setting out the reasons for the approval (s.170(3)(c)).

Under s.13 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1989 (ACT) (the Judicial Review Act) a person aggrieved by a decision can apply in writing for a written statement of reasons for certain government decisions. For Commonwealth decisions, s.13 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) confers the same right.

[12.8.4] Tribunal review of a decision

In August 2008 the ACT Legislative Assembly passed the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act 2008 that amalgamates a number of existing tribunals, including the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), and consolidates them into a single administrative tribunal, the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT). The new tribunal commenced on 2 February 2009.

Like the now abolished AAT, ACAT reviews the merits, rather than the lawfulness, of a decision. That is, the tribunal 'stands in the shoes' of the original decision maker and decides the matter anew, according to the facts and circumstances as they exist at the date of the tribunal's review, that is not at the date of the original decision.

An important aspect of ACAT is that it differs from a court as a method for dispute resolution in the following ways: whereas court proceedings can take years for resolution, can be expensive in terms of filing fees and ongoing costs in legal fees, ACAT by comparison is characterised by speedy processes, minimal fees, self representation (or lawyer representation if you wish), reduction of formalities and not so much reliance on the technical rules of evidence.

Not all decisions of all government agencies or authorities can be reviewed by ACAT. There must be a right to have the decision reviewed by the tribunal stated in the relevant legislation. For example:

· Environment Protection Act 1997 (s.135, Schedule 3)—a decision to grant an environmental authorisation

· Water Resources Act 2007 (s.94, Schedule 1)—a refusal to issue a licence to take water

· Planning and Development Act 2007 (ss.407-410, Schedule 1)— a decision to approve or refuse a development application

· Tree Protection Act 2005 (s.107, Schedule 1)— a decision to refuse or approve the registration of a tree

· Heritage Act 2004 (ss.111-114, Schedule 1)—a decision to register or not register a place or object.

Even then, some decisions are specifically exempted from review. For example, single residential development applications, as a code track application, are generally exempt from review by the ACAT (Chapter 13 and Schedule 1 of the Planning and Development Act) (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 3). It is necessary to seek advice on this point from a lawyer, such as the EDO, or from the Registrar's office at the ACAT as to whether the decision is reviewable by the tribunal.

The form, 'Application for Review of Decision', is available from the tribunal registry and online. An application under the Planning and Development Act 2007 for review costs $178.00. Application for review of decision under other environmental Acts is $255.00 (Attorney-General (Fees) Determination 2009, 1 July 2009, as amended). Check with the tribunal for any changes in the fee structure. Usually you have 28 days from the date of the decision to lodge an appeal (rule 12 ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal Procedure Rules 2009), but again, check with the tribunal (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[12.8.5] Supreme Court of the ACT

As well as hearing appeals on questions of law from ACAT hearings, the Supreme Court can review certain decisions made by government agencies without an initial ACAT hearing. It is necessary to look at the legislation under which the decision was made to determine whether a case can be taken directly to the Supreme Court. The Judicial Review Act provides a right of judicial review of the lawfulness of a wide range of ACT government decisions and those cases are heard in the ACT Supreme Court. In contrast to the ACAT, Supreme Court hearings tend to be more costly and are held in a more formal legal environment.

The Supreme Court Registrar can assist with information on filing fees. In some instances filing fees may be reduced in public interest matters.

A decision on the most appropriate judicial venue needs to be made on a case by case basis; considering what legislation is involved, the level of potential cost and the contrasting natures of the venues.

[12.8.6] Barriers to pursuing legal actions

…to assume that competitive instincts are aroused only by concern for material wealth would be to ignore history. Much of the progress of mankind has been achieved by people who have sacrificed their own material interests in order to champion ideals against fierce resistance. The recent Australian experience is that, in cases where ideologues have been able to gain access to the court, cases have been hard fought and professionally conducted. Ogle v Strickland (1987) 13 FCR 36 (Federal Court of Australia)

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to detail the procedural barriers in pursuing legal redress to achieve an environmental outcome. Suffice to say there are 'procedural barriers' including standing and security for costs. Procedural barriers mean hurdles you must jump before the substance of your legal arguments is heard.

Standing is the right to have an issue heard before a court or tribunal. Standing is often only available to a 'person aggrieved'. Traditionally this has meant that only persons directly affected by a decision or an action have a right to take legal action. In a long line of cases environmental groups pursing a legitimate public interest goal, for example, preventing the export of native forests as woodchips, have had to justify that they are 'a person aggrieved'.

In Save The Ridge Incorporated v Australian Capital Territory & Anor (2004) ACTSC13 the ACT Supreme Court considered whether the community group Save The Ridge had standing to bring the issue before the court. In considering this Justice Crispin decided that the group's objectives as outlined in their constitution were relevant.

Under s.475 of the Commonwealth Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) any 'interested person' (individual or organisation) can apply for an injunction to remedy or restrain a breach of the Act. An interested person is defined as a person whose interests have been or would have been affected, or has engaged in a series of activities for protection or conservation of, or research into, the environment in the previous two years. Under s.487 the term 'person aggrieved' for judicial review under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) is similarly extended.

Even if a group can establish standing to bring an action they may be prevented from doing so if security for costs is required. Security for cost is where a party to the proceeding, when challenged, must provide evidence that it has sufficient funds to cover costs in the event that it loses. In Truth Against Motorways v Macquarie Investments 2000 FCA 918 the Federal Court decided that TAM had to provide a security for costs and Hely J rejected the argument that the public interest nature of the litigation mean that the Court should not require security.

If you and your group are at the stage of considering seriously a Supreme Court challenge then you should be seeking opinions of barristers and be in regular communication with a solicitor. Going to court means being mentally prepared for the expense and time consuming nature of proceedings. It is one strategy for achieving better environmental outcomes and it should not be ignored but it also should not be seen as a silver bullet.

[12.9] Risks of speaking out—defamation

[12.9.1] What is defamation?

Defamation occurs when a 'publication' (see Publication), identifying a person, conveys a meaning that tends to:

· lower that person's reputation in the estimation of right-thinking members of society

· lead people to ridicule, avoid or despise that person

or

· injure that person's reputation in business, trade or profession.

However, even if what you have said is defamatory, there may be a defence available, for example, based on justification (truth), fair comment, or privilege (absolute or qualified). A person can take action for defamation without any proof of any actual damage having been suffered as a result of the injury to their reputation.

Defamation law is based on common law principles (principles developed through case law), supplemented by statutory provisions.

In 2004 the Attorneys-General of the states and territories agreed to support the enactment of uniform defamation laws in their respective jurisdictions. At the time of this agreement, defamation laws differed from jurisdiction to jurisdiction in Australia. In 2005 uniform defamation laws were enacted in each state and territory, commencing in January 2006. ACT included the provisions of the uniform model defamation law into the Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 (ACT) (the Civil Wrongs Act).

[12.9.2] Elements of defamation

There are three main elements that the party bringing the action must establish about the allegedly-defamatory material, that it:

· is published

· identifies a particular person

· has a defamatory meaning.

Publication

Material is deemed published if it is communicated to anyone other than the party who claims to have been defamed. Material does not have to be published in a newspaper, any of the following could fall into the legal definition of publication:

· comment in a conversation with a person (other than the person defamed)

· media release

· comments made during a speaking engagement

· a letter

· a banner

· material published on a website

· material contained in an email, including internal emails.

Further, it is not a defence to say you are simply repeating what someone else has already published. Republication of another person's defamatory statement can give rise to a new and separate action for defamation.

An identifiable person

The defamed person need not be explicitly identified. If certain recipients of the publication had knowledge of special facts or circumstances at the time of publication, which enabled identification of the individual, then this is sufficient. Further, if the published material/statement identifies someone falsely, then the person who has been wrongly identified can also establish they have been wrongly defamed.

Only living persons can be defamed (s.122 Civil Wrongs Act). Significantly, since the changes implemented in 2006, corporations (who are not public bodies) employing more than 10 people can no longer sue for defamation (s.121 Civil Wrongs Act). This will severely limit large corporations suing people who speak out. However an individual director of a large company may still sue for defamation if the defamatory material points to him or her in particular.

Defamatory material

Material is considered to be defamatory when judged against community standards. The test applied by the court is whether an ordinary reasonable person would have understood the material as:

· lowering that person's reputation in the opinion of right thinking members of society

· leading people to ridicule, avoid or despise that person

or

· injuring that person's reputation in business, trade or profession.

[12.9.3] Defences to defamation

The defences to a defamation action are designed to balance the competing public interests of freedom of speech and the protection of an individual's right to reputation. The defences of most relevance in relation to environmental comment are:

· justification/truth

· fair comment

· honest opinion

· privilege (absolute or qualified).

These defences are either set out in legislation (such as justification, privilege and honest opinion, ss 135, 137, 139A and 139B Civil Wrongs Act) or are available at common law (such as fair comment).

Justification/truth

The starting point is that it is a defence to publish material that is true. Previously in the ACT, it was not sufficient to prove that the material was true; the publication of the material also had to be for the public benefit.

However, under s.135 of the Civil Wrongs Act, there is a defence that the defamatory imputations carried by the matter of which the plaintiff complains are 'substantially true'. The term 'substantially true' is defined in s.116 to mean 'true in substance or not materially different from the truth'. In all other respects, the common law principles apply.

Fair comment

The common law provides a defence of fair comment on a matter of public interest which protects freedom of expression, long regarded as a basic right. Under this defence the comment must be:

· relate to a matter of public interest

· based on fact or other proper material

· comment, not a statement of fact

· fair, in the sense that it is the honest expression of the person's real view—the defendant must prove that the comment is objectively fair, that is, that an honest or fair-minded person could hold such an opinion, even if it is exaggerated, prejudiced or obstinate.

The common law defence may be defeated by proof of malice.

Honest opinion

The statutory defence of honest opinion is modelled on the common law defence of fair comment, which continues to apply.

Section 139B of the Civil Wrongs Act provides a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that:

· the matter was an expression of opinion of the defendant rather than a statement of fact

· the opinion related to a matter of public interest

· the opinion was based on 'proper material'.

Proper material is defined in s.139B(4) to mean material that is substantially true, was published on an occasion of absolute or qualified privilege (see Privilege – absolute and qualified, below), or was published on an occasion that attracted the protection of a defence under s.138 (publication of certain public documents), s.139 (fair report of proceedings of public concern) or the defence of fair comment at general law.

Privilege – absolute and qualified

It is a defence to an action for defamation if it can be shown that at the time of communication the relevant information was privileged. If the publication is privileged the truth of the defamatory material is irrelevant. There are two levels of privilege, absolute and qualified.

The publisher of absolutely privileged material enjoys a complete defence from defamation proceedings. The defence can be relied on even if the material was published maliciously. The two most commonly raised instances of publications protected by absolute privilege are:

· statements made in the course of parliamentary proceedings and in official parliamentary papers—the term parliamentary proceedings extends to parliamentary committee reports and inquiries

· statements made in the course of judicial or quasi-judicial proceedings.

Absolute privilege only attaches to the primary publication of absolutely privileged materials, for example, in parliament or the court. The Civil Wrongs Act confirms the common law defence of absolute privilege. Section 137 states that material published in the course of proceedings of parliamentary bodies, Australian courts and tribunals attract absolute privilege.

The defence of qualified privilege covers a range of different situations where, in the interests of protecting the essential flow of information, a limited or qualified privilege is allowed by the law. Broadly speaking, these are situations in which the publisher or speaker has an interest in or duty to provide information on a particular subject to a person who has an interest in or duty to receive that information (s.139A Civil Wrongs Act). An example of qualified privilege might be where a minister or official, who is going to make a decision on an issue, has called for submissions and views from interest groups.

Malice or improper purpose will defeat the defence of qualified privilege.

A fair and accurate report on proceedings of a public concern, such as what is spoken in parliament or presented in courts, is protected by qualified privilege (s.139 Civil Wrongs Act). To attract the privilege a matter must be published honestly for the information of the public. And the report must indeed be both fair and accurate. The report need not be complete but it must be neutral and balanced. In other words, you must be careful not to quote selectively from the material.

[12.9.4] Avoiding defamation actions

Following are some tips for avoiding defamation actions:

· fight the issue not the personality—ensure that any communication does not involve any form of personal criticism or attack on an identifiable individual

· ensure the truth of any representation made can be verified with original documentation or witness statements—if you are unsure of the truth of a representation, do not make it

· where possible attempt to include the factual basis of a representation along with the published material

· be able to readily identify an issue of public interest or benefit relating to a representation

· think before you click when sending email—do not write anything in an e-mail that you would not feel comfortable about seeing published on the front page of a national newspaper; have a colleague scan any material intended for public release; in many cases, an independent mind will see potential defamatory material when you may not.

[12.10] Risks of taking action—criminal charges

[12.10.1] Introduction

Protest is not uncommon in Canberra city, the site of the Commonwealth Parliament. If you are charged with an offence it is likely you will be charged under Commonwealth law, not ACT law, if you are in the Parliamentary Triangle or on Northbourne Avenue. Both of these are designated as Commonwealth land. The Commonwealth planning agency, the National Capital Authority, has produced a booklet, The right to protest a guide, which delineates broad boundaries between Commonwealth and ACT land, indicating which jurisdiction will apply (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 2 for discussion of Commonwealth and territory land). The ACT Human Rights Act 2004 (see [12.10.3] Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT)) will only apply if you are clearly protesting on territory land.

[12.10.2] The full force of the criminal law

The application of the criminal law to matters in which individuals are seeking environmental outcomes can seem rather odd; but it is an outcome which people committed to taking action must be prepared for.

The most common charges are: obstruction of a police officer in the exercise of his/her duty; resist, hinder or obstruct arrest; trespass; assault; and in forestry matters, entering a prohibited area, or failure to obey a direction. Getting arrested should not be undertaken lightly. For instance, pleading 'not guilty' from the time of being charged to the final clearing of your name can take from six months to two years for a resolution.

Due to the heavy workload of the Magistrates court, the criminal justice system rewards persons who plead guilty straight up. If you have no prior convictions and can provide character references, you may receive a few hundred dollar fine and 'no conviction recorded.' However, depending on the circumstances of the offence, you may end up with a fine and a criminal record. Section 33 of Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT) sets out the factors a judge will take into account when sentencing you, including the nature and circumstances of the offence, any injury, loss or damage resulting from the offence, the cultural background, character, antecedents, age and physical or mental condition of the offender.

It is very important if you are charged with a criminal offence to seek legal advice before you plead 'guilty' or 'not guilty'. You cannot be punished for seeking legal advice regarding your right to know what you have been charged with and the potential consequences. This is a fundamental premise of the criminal justice system—you have a right to know the case against you. It can be useful to have a video camera running, although be prepared that police may temporarily confiscate video cameras at the time of arrest.

[12.10.3] Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT)

There is no right to a clean environment provided for in the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT), The Human Rights Act declares the following protections:

· everyone has the right to move freely within the ACT (s.13)

· everyone has the right of peaceful assembly (s.15(1))

· everyone has the right to freedom of expression—this right includes the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of borders, whether orally, in writing or in print, by way of art, or in another way chosen by him or her (s.16(2)).

For an activist charged with a criminal offence under ACT law the Human Rights Act provides very limited protection and is largely untested in a court in the ACT regarding protest and environmental action.

[12.11] Non Violent Direct Action (NVDA)

NVDA, as practiced by the modern environmental movement, draws on the Quaker tradition of bearing witness to raise awareness and bring public opinion to bear on decision-makers. When planning and participating in a non-violent direct action remember that you are not out to make enemies but to win people over to the issue. Non-violence means in taking action you are:

· peaceful

· considerate

· compassionate

· gentle

· acting in the interests of the group, not in the heat of the moment.

It is beyond the scope of this handbook to discuss the legal aspects of non-violent direct action. There are however many resources on NVDA.

[12.12] Conclusion

By taking action to protect the environment, groups and individuals directly confront ingrained values and behaviours—self-interest, apathy and greed. People do not take kindly to being told that driving a car is polluting when it is what gets them to work, which pays the bills, which feeds the children. However there are other ingrained values that environmental groups and individuals can appeal to, for example, self interest in the sense of children being a part of the future generation.

A group's strengths in taking action include the use of both logical and lateral thinking, respect for the goals of the group and strategic use of the eight elements outlined at the beginning of this chapter, including legal and parliamentary tools. Governments and corporations are capable of change and it's the people who change them.