5 - Biodiversity Conservation

Contributors – Hanna Jaireth and Geoff Robertson

Last Updated – March 2009

[5.1] Introduction

Biodiversity exists everywhere — including in Canberra Nature Park, on rural properties and in urban Canberra. Legislation and legal agreements for biodiversity conservation are aimed at protecting and managing the diversity of our ecosystems, species, and genetic diversity—the components of biodiversity.

Many territory Acts affect biodiversity, including legislation for land use planning and development, tree protection, the keeping of native and introduced animals, wood collecting, and conservation generally. The two critical pieces of legislation are the ACT's Nature Conservation Act 1980 and the Commonwealth's Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. But biodiversity can also be protected under various agreements between governments and stakeholders that are not expressed in legislation. Some regional and territory-wide initiatives, such as the proposed nomination of the ACT as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, and the 'Kosciuszko to Coast' project, may also benefit biodiversity, but are unlikely to involve any legislative impacts. The first section of this chapter lists some of these non-legislative instruments that provide the policy context within which the legislation, summarised in parts two and three, operates.

Understanding the legislation, regulations, and processes that operate in the ACT enables citizens to monitor whether land owners and managers, including the ACT government, are fulfilling their legal obligations to protect the territory's biodiversity. Knowledge of biodiversity law and practice also enables citizens to participate constructively in public consultations and debates, and take other action that might lead to greater protection of our environment. Citizens should be aware of the limits that are imposed on domestic activities such as keeping animals, growing certain plants and tree removal. Public assistance in reporting activities such as illegal fishing, the taking of plants or wood from reserves and the keeping or trapping of native animals can help to protect biodiversity in the ACT. Informed advocacy may also lead to better education, policing, and prosecution where appropriate.

[5.2] Mechanisms for protecting biodiversity

[5.2.1] Regional-scale biodiversity conservation

A small part of the ACT falls within the Australian Alps sub-bioregion, while the remainder falls within the South-Eastern Highlands sub-bioregion. The ACT government is a party to the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperative Management of the Alps Parks and participates actively in the Alps Cooperative Management Program. The Alps bioregion is recognised by the World Conservation Union as one of the 167 world centres of biodiversity. Parts of this bioregion may be nominated for listing as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in coming years.

The ACT is part of the Murrumbidgee River Catchment. Its Management Authority and the Murrumbidgee Catchment Management Board oversee the implementation of the NSW Murrumbidgee Blueprint, which is managed in cooperation with ACT bodies. The value of a regional planning approach is recognised in the ACT Nature Conservation Strategy, particularly in relation to habitat linkages and wildlife corridors. Regional connectivity is also recognised in the report of the 1999 Natural Heritage Trust-funded project 'Corridors for Habitat and Biodiversity Conservation in the ACT with Links to the Region' and the 2002 Planning Framework for Natural Ecosystems—NSW Southern Tablelands and ACT.

In March 2006 an Agreement for the ACT – NSW Regional Management Framework was concluded between the ACT and New South Wales governments. The ACT Natural Resource Management Plan 2004–2014, and the ACT Natural Resource Management Council's more recent draft plan, Bush Capital Legacy, are strategic documents which set targets for biodiversity conservation, and identify actions and monitoring that need to be done. Funding to implement the Council's strategy will be drawn from the Caring for Our Country program which replaces the former Natural Heritage Trust.

As noted in [5.12] Table 1, high quality box woodlands are critically endangered nationally, and are endangered in the ACT. The largest and best surviving stands of these woodlands occur primarily in the ACT/Queanbeyan/Goulburn region. Similarly, there are some surviving patches of the endangered natural temperate grasslands of south-eastern Australia, and their associated flora and fauna, in the ACT and New South Wales.

[5.2.2] Territory scale biodiversity conservation

More than half of the territory is in designated protected areas and is managed to maintain and protect its biodiversity, and associated natural and cultural resources and values. But biodiversity in the territory is also under pressure—already two ecological communities and at least 17 plant and animal species are endangered, and 14 species are vulnerable, as listed in [5.12] Table 1. Extreme weather events in recent years have impacted negatively on biodiversity, such as drought, heavy rains, dust storms and bushfires. These may be related to longer term climate change. Urban expansion, habitat fragmentation, and pest plants and animals also threaten biodiversity and agriculture in the territory.

Both the Territory Plan and the National Capital Plan protect biodiversity by protecting significant wilderness areas, parks and reserves, hills and ridges, urban open space, river corridors and wildlife corridors. See ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapters 2 and 3 for a discussion of planning and development in the ACT and ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 4 for environmental assessment at both the strategic and individual development levels. The chapters following this one deal with biodiversity conservation in relation to trees (ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 6), public land (ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 7), water (ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 8) and heritage (ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 9).

The draft ACT Natural Resource Management Plan, Bush Capital Legacy, provides various strategies for the protection and management of the ACT environment, including the creation of wildlife corridors. One of its targets is that 'biodiversity decline is halted, then sustainably managed to ensure resilient ecosystem functioning' (p46). The ACT government's sustainability policy, People Place Prosperity recognises 'life has intrinsic value and that ecological processes and biological diversity are part of the irreplaceable life support systems upon which a sustainable future depends' (p13). .

The ACT has interests in regional and continental-scale wildlife corridor projects such as the Australian Bush Heritage-initiated 'Kosciuzsko to Coast' project, which involves a broad partnership of government agencies, catchment authorities and large and small conservation groups; and 'the Great Eastern Ranges Initiative' wildlife corridor proposal agreed by the Environment Protection and Heritage Council in June 2007. The Conservation Council ACT Region argues that in addition to current Territory and National Capital Plan corridors, more and better woodland, grassland and riparian corridors should be created through urban Canberra. Lobbying may continue for such corridors to be recognised as a conservation overlay in both plans.

The ACT has a laudable record of community participation in all aspects of biodiversity conservation, such as on-ground work, public education, research, and advocacy. The territory has several sub-catchment community organisations involved in prioritising the implementation of agreed sub-catchment plans, for example, for Tuggeranong-Tharwa, Weston-Woden, and south-west rural ACT, and the upper Murrumbidgee. In recent years the territory has had about 16 urban Landcare, 14 Park Care, four rural Landcare groups, and more than 100 Waterwatch and Frogwatch volunteers. Their work is complemented by that of national organisations such as Greening Australia and Conservation Volunteers Australia. The peak ACT body, Conservation Council ACT Region, and many of its member groups have a strong history of advocacy, education, research and on-ground work and generally improving community understanding of flora and fauna issues.

While some environmental groups are sometimes dissatisfied with the lack of policy responsiveness to the often expert submissions they have made and views they have expressed during consultation processes, so too industry and other stakeholders are sometimes critical of various planning and development decisions that the ACT government has taken. Some of these concerns have been taken up by the ACT Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment, and some have been pursued through the courts, with mixed success. See ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 12 for the legal implications of taking action and the ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts for contact details for the groups mentioned above.

[5.2.3] Local scale biodiversity conservation

Local scale biodiversity conservation can concern small areas of vegetation or even individual trees, and can involve various land uses. Local scale ecological connectivity can reduce the environmental pressures created by urban development. For example, indigenous trees that are retained in ecological communities, native grasslands and grassy woodland paddocks, and remnant indigenous trees that have been retained in the urban landscape, all serve a biodiversity purpose. Other introduced trees, such as arboreta for research and other purposes, and trees in rural areas, public landscapes, street trees and home gardens, while generally not serving a biodiversity function (except in the case of certain native trees) often have an amenity and heritage value and perform a range of ecological services. Debate continues amongst ecologists, landscape architects and heritage stakeholders, amongst others, about how the territory should change the exotic/indigenous balance in its urban forest. The ACT government has an ambitious long-term tree replacement program, and also replaces trees that have died as a result of drought, old age or other causes (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 6 on tree preservation).

Local scale biodiversity conservation can be protected under territory planning and implementation processes. For example, management plans for public lands, master plans, and neighbourhood plans usually address local-scale environmental protection. So too can development application assessments, and lease management. The territory's Design Standards for Urban Infrastructure and Plant Species for Urban Landscape Projects are also relevant. They have taken into account the recommendations made in the Canberra Urban Parks and Places-commissioned report Wildlife Corridors and Landscape Restoration: Principles and Strategies for Urban Nature Conservation (1998).

[5.3] Nature Conservation Act 1980 (ACT)

[5.3.1] Introduction

The purpose of the Nature Conservation Act is to 'make provision for the protection and conservation of native animals and native plants, and for the reservation of areas for those purposes'.

It should be noted that at the time of writing the Act was being reviewed, and amendments or replacement legislation was expected to follow the completion of the review.

The Nature Conservation Act creates the office of Conservator of Flora and Fauna and the ACT Parks and Conservation Service (Div.2.1). It provides for a Nature Conservation Strategy for the ACT (Div.3.1), and special protection measures for declared flora and fauna. It provides for declarations identifying species and ecological communities at risk (Div.3.2), management agreements (Part 10), directions based on declarations, and a regime of action plans (Div.3.4) and licences (Part 11). It also establishes the Flora and Fauna Committee (Div.2.2). The Act and its subordinate legislation also provides for monitoring, compliance and enforcement activities.

Public land can be designated as a reserve under the statutory National Capital Plan and the TP made under the Australian Capital Territory (Planning and Land Management) Act 1988 (Cth) and the Planning and Development Act 2007 (ACT), respectively (see [7.2] Creating public land).

[5.3.2] The conservator and the service

The Conservator of Flora and Fauna (conservator), or the person for the time being exercising the conservator's duties, is a public servant appointed under the Nature Conservation Act (s.7). At the time of writing the conservator is the Chief Executive of the Department of Environment, Climate Change, Energy and Water. The conservator has statutory powers under the Nature Conservation Act, the Planning and Development Act (see [3.4.5] Merit track approval process and [3.4.6] Impact track approval process) and the Tree Protection Act 2005 (ACT) (see Handbook Chapter 6).

Under the Nature Conservation Act, the conservator:

· administers the licensing system for the taking of native plants and animals (Part 11)

· manages the nature reserve system in the ACT (Part 8)

· develops the ACT Nature Conservation Strategy (Div. 3.1)

· protects and conserves threatened species and ecological communities (Div 3.2).

The Act also gives power to the conservator to regulate access to protected areas in the ACT, for public safety or conservation management purposes (see [7.7] Activities prohibited on public land).

The Act also establishes the Australian Capital Territory Parks and Conservation Service (service) (s.12). The service comprises conservation officers, including the rangers we see in parks and reserves (s.8). The role of the service is to assist the conservator in the exercise of his or her functions under the Act. The conservator may delegate any of his or her functions under the Act to conservation officers (s.11), who also have specified investigation and enforcement powers.

A conservation officer can ask a person to leave a reserved area if they are acting in an offensive manner, or are reasonably suspected of having acted in an offensive manner, or if they are creating a public nuisance (s.69). A conservation officer may enter land and carry out investigations and examinations in relation to native animals or plants if he or she thinks that it is necessary or desirable to ensure their protection and conservation. However, the officer must receive written permission from the occupier to do this or give the occupier 24 hours written notice (s.59). Conservation officers also have powers of inspection, search and seizure in relation to land, premises, vehicles and vessels (ss.130–133). They can serve infringement notices under the Magistrates Court (Nature Conservation Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005 for breaches of the Act.

The service also does research and monitoring work, and assists the many volunteer environment and conservation organisations that contribute to biodiversity conservation in the ACT, including organisations in the Parkcare network.

The conservator also has a range of powers and functions under other Acts, such as under the Tree Protection Act (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 6) and the Planning and Development Act (see [3.4.5] Merit track approval process and [3.4.6] Impact track approval process).

[5.3.3] Flora and Fauna Committee

The Flora and Fauna Committee (committee) established under the Nature Conservation Act (s.13) provides advice to the minister on nature conservation and performs other duties prescribed to it under the Act (s.14). A bi-annual report of the committee's activities is accessible on the web, and more information is available from the committee secretary. The minister can give the committee written general directions. The conservator has to include a copy of these, and information about the actions taken to implement them, in his or her annual report (s.15) (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts.)

Appointees to the committee are scientists with expertise in ecology or biodiversity, and at least two must not be public servants (s.17). Seven members are appointed by the minister on a part-time basis and hold office for up to three years, but can be reappointed. Until 30 June 2009 the appointees include: Professor Arthur Georges (chair), Dr Penny Olsen (deputy chair), Dr Margaret Kitchin, Dr Barry Richardson, Dr Richard Norris and Mr Paul Stevenson.

[5.3.4] Nature Conservation Strategy

The Nature Conservation Strategy is a policy document required by the Nature Conservation Act (Div.3.1). It includes chapters on:

· the conservation of biological diversity—through bioregional planning, reservation, off-reserve conservation, conservation of threatened species and communities, and monitoring of biodiversity

· the management of ecological threats—pest plants and animals, changed fire regimes, degradation of aquatic systems, and decline and loss of native vegetation

· community involvement

· implementation.

In 2008 the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council was reviewing the National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity. The results of that review are expected to influence the outcomes of a proposed review of the ACT's Nature Conservation Strategy.

[5.4] Identifying species and communities at risk

[5.4.1] Declaration of species or community as endangered or vulnerable

The Flora and Fauna Committee can recommend that a species should be declared:

· endangered, if it is likely to become extinct in the ACT region unless the threats to its abundance, survival or evolution cease, or if its numbers or habitats have been reduced to such a level that the species is in immediate danger of extinction in the ACT region

or

· vulnerable, if within the next 25 years it is likely to become endangered in the ACT region unless threats to its abundance, survival or evolution cease (ss.35 and 38 and guidelines made thereunder, the Threatened Species and Communities in the ACT Criteria for Assessment in the Nature Conservation (Criteria and Guidelines for Declaring Threatened Species and Communities) Determination 2008 (No 1) DI2008–170), check the Legislation Register (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

The committee can recommend that an ecological community be declared endangered if it is in immediate danger of extinction in the ACT region unless the threats to its distribution, composition and viability as an ecological unit cease. The committee can also recommend that a process be declared threatening if it threatens the survival abundance or evolution of a species or community in the ACT region.

Any person or organisation may make a written nomination on an approved form, requesting that the committee recommend the declaration of a species, ecological community or threatening process. The request must be accompanied by a statement containing the reasons why the applicant considers that the declaration should be made (s.39).

Nominations for the committee's consideration are accepted in accordance with the criteria and guidelines in DI2008–170. The committee assesses the application and may then make a recommendation to the minister that he or she make a declaration.

If the recommendation is accepted the minister makes a declaration under the Nature Conservation Act (s.38) that the species or ecological community is vulnerable or endangered. All declarations, which are made in the form of disallowable instruments, are accessible on the web through the ACT Legislation Register (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts). The most recent list of declarations is in the Nature Conservation (Species and Ecological Communities) Declaration 2008 (No 2) DI2008–53. A comparison of declarations made under the Nature Conservation Act and protective listings by the New South Wales and Commonwealth governments is at [5.12] Table 1.

(New South Wales populations of the

Gang gang cockatoo

are endangered or vulnerable -- see [5.12] Table 1)

In its various conservation strategies, particularly the woodland, grassland and riparian action plans, the ACT government gives special attention to species that are listed in other jurisdictions, but not in the ACT. In the action plans, these species are described as uncommon and or rare. Mention is also made in the action plans of lists of other uncommon and or rare species in the ACT which receive special management attention.

[5.4.2] Threatened ecological communities

Currently two threatened ecological communities are listed in the ACT: Natural Temperate Grasslands, and Yellow Box/Red Gum Grassy Woodland (DI2008–53). Both are also listed under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), and box woodland is also listed in New South Wales. However, the definitions used in the different jurisdictions differ. For example, natural temperate grasslands defined under the EPBC Act include the ACT's montane grasslands, whereas the ACT listed ecological community does not. Natural temperate grasslands are afforded some protection under New South Wales native vegetation legislation.

Recovery teams consisting of government agencies, experts and community representatives, may be established to identify, protect, manage and recover threatened ecological communities and species. One successful recovery team is the Natural Temperate Grasslands of the Southern Tablelands of NSW and the ACT Recovery Team, which has representatives from the ACT and New South Wales governments, catchment management authorities, the New South Wales Farmers Federation, and community groups such as Friends of Grasslands and Greening Australia. This team not only provides expert advice but used funding to employ a project officer to map potential grasslands remnants, to identify new sites, and to bring new sites under conservation management.

[5.4.3] Declaration of protected and exempt flora and fauna

The conservator may, under the Nature Conservation Act (s.34), declare that certain fish, invertebrates, animals and plants are protected, and that certain animals are exempt from protection. In making such a declaration the conservator takes into account the need to protect and ensure the welfare of native wildlife in the ACT, to conserve the significant ecosystems of the ACT, New South Wales and Australia, and to safeguard the specialised welfare and security requirements of the animal, plant, fish or invertebrate (except in relation to exempt animals). The most recent declaration of this type, Nature Conservation Declaration of Protected and Exempt Flora and Fauna 2002 (No. 2) DI2003‑6, is accessible on the ACT Legislation Register.

As each jurisdiction works somewhat independently, there is not necessarily a common view about the status of each listed species. In addition, in some jurisdictions, there are different priorities for listing species. For example, a particular species may not be listed if to do so would neither enhance nor further threaten its survival. However, individuals making submissions about the need to protect the habitat of particular species, not listed as threatened in the ACT, might use as evidence their status in other jurisdictions. Drawing on the information used by another jurisdiction might assist in the nomination and assessment process.

[5.4.4] Declaration of prohibited and controlled organisms

Under Part 6 of the Nature Conservation Act, the conservator may declare organisms of a particular kind to be prohibited or controlled. This provision appears to have been little used. In making the declaration, the conservator has to consider the need to protect native animals and plants in the territory and to conserve significant ecosystems in the ACT, New South Wales and Australia. Penalties apply to the possession of a prohibited organism without a licence.

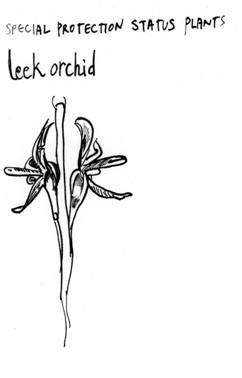

[5.4.5] Declaration of special protection status

A declaration of special protection status is the highest level of statutory protection that can be given to flora and fauna under the Act, and provides for increased penalties for unauthorised activities and tighter licensing constraints. Under s.33 of the Nature Conservation Act, the conservator must make a written declaration of special protection status for native plants and animals if they are declared endangered by the minister under s.38, or if the conservator believes on reasonable grounds they are threatened with extinction.

The conservator may also make such a declaration about members of a migratory species whose protection is the object of an Act of the Commonwealth or an international agreement entered into by the Commonwealth (s.33). When making these declarations the conservator considers the conservation status of the species, not only in the ACT, but also in New South Wales and Australia.

The conservator made the most recent declaration on 2 May 2005, in Nature Conservation (Special Protection Status) Declaration 2005 (No 1) DI2005–64. The list of species with special protection status includes migratory animals and birds, marine and land mammals, birds, amphibians, fish and reptiles that are threatened with extinction, including the ACT's endangered species.

[5.5] Protecting biodiversity

[5.5.1] Action plans

The Nature Conservation Act requires the conservator to prepare a draft action plan in response to each declaration of a threatened species or ecological community, or threatening process (Div.3.4). Action plans include proposals to ensure, as far as is practicable, the identification, protection and survival of the species, or the ecological community; or proposals to minimise the effect of any process which threatens any species or ecological community. For example, action plans include the criteria for the declaration, a scientific description of the species or community, information on its distribution, conservation status locally, nationally and internationally, plus the conservation objectives and proposed protection measures. As noted above, management considerations are addressed in a regional context.

Each action plan is first released as a draft for public comment. The conservator has to publish a notice of the development of a draft action plan in the ACT Legislation Register and a newspaper, including information on where the drafts are available for public inspection. The consultation period has to be at least 21 days but can be longer (s.41). The conservator then prepares the action plan, taking into account any comments, and puts a notice in the ACT Legislation Register and the Canberra Times, stating that copies of the final plan are available and accessible on the web, as are fact sheet summaries of most of the plans (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

Several important action plans have been released in recent years, including:

· Woodlands for Wildlife: ACT Lowland Woodland Conservation Strategy (Action Plan No.27)

· ACT Lowland Native Grassland Conservation Strategy (Action Plan No.28)

· ACT Aquatic Species and Riparian Zone Conservation Strategy (Action Plan No.29).

Action plans are important strategic and reference documents for sustainable development. They are implemented by government working in partnership with stakeholders, through the mechanisms appropriate for the land tenures to which the strategy document applies. Action plans inform the development of management plans for public land and urban planning policy development and decision-making. They have also been cited in evidence by stakeholders in legal challenges to government planning decisions, for example, in Thornbrook Pty Ltd and Cowper Pty Ltd v Commissioner for Land & Planning and Ors (2002) ACTAAT 7 (27 March 2002).

[5.5.2] Offences

Part 4 of the Nature Conservation Act protects animals and fish by setting up a range of offence provisions. For example, a person must not, except in accordance with a licence (see [5.5.4] Licences) or pursuant to a valid defence:

· interfere with the nest of a native animal, or with anything in the immediate environment of such a nest, so that the interference places the animal or its progeny in danger of death or not being able to breed (s.43)

· kill or take a native animal whether dead or alive (ss.44 and 45)

· keep, sell, import or export an animal (other than an exempt animal) or live fish (ss.46–48)

· release a native animal from captivity if the release places the animal in greater danger of injury or death than if it had been kept in captivity, or release a native or other animal that threatens the survival, abundance or evolution of any species of native animal (animal in this context includes a fish) (s.49).

Offence provisions also apply for the protection of plants under Part 5 of the Act. For example, a person must not, except in accordance with a licence, take a plant that has special protection status, or which is a protected native plant or a native plant growing on unleased land (s.51). It is also an offence to sell a protected native plant, or import into or export from the territory a protected native plant for the purposes of sale or trade, without a licence or under an exception in the Nature Conservation Act (s.53) Native timber is also protected, and (subject to certain exceptions, where it is standing on unleased land, or on leased land outside the urban area) must not be felled without a licence or without a reasonable excuse (s.52). Nor must fallen native timber on unleased land be damaged without reasonable excuse (see [6.6.2] Nature Conservation Act 1980).

Exceptions and/or defences to prosecution are available under the Act. For example, it is a defence to a prosecution for interfering with a nest of a native animal if the defendant believed, on reasonable grounds, that the danger of death or not being able to breed did not exist, or that the place, structure or object alleged to have been interfered with was not a nest, or was not in the immediate environment of a nest (ss.43(3) and (4)). It is not an offence to kill an animal if it is endangering a person (ss.44(2)).

During the financial year 2007–08, ten investigations were conducted. Two matters were referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions, two were referred to other agencies, two alleged offenders were issued with a formal caution, and three other incidents were under active investigation. Minor offences, such as walking dogs off leashes in a reserve area, riding motorcycles in reserves, and vandalism (such as graffiti and fence damage) were recorded for information only. Regular liaison between service rangers and the Australian Federal Police Rural Patrol was reported in the annual report of TAMS (See ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[5.5.3] Penalties

The Nature Conservation Act includes various offence and penalty provisions. Penalties under the Act can be substantial. For example, the maximum penalty for interfering with a native animal nest, as proscribed, can be up to 100 penalty units, or imprisonment for one year, or both, if the animal has special protection status. If the animal does not have special protection status, the maximum penalty can be up to 50 penalty units, imprisonment for six months or both. At the time of writing, under the Legislation Act 2001 (ACT), a penalty unit was $110 for an individual and $550 for a corporation.

The maximum penalties for clearing native vegetation in a reserved area which causes serious harm vary. For example, if the offender was:

· reckless, the penalty can be up to 2,000 penalty units, imprisonment for five years or both

· negligent, the penalty can be up to 1,500 penalty units, imprisonment for three years, or both (s.77).

If charged with a strict liability offence, the maximum penalty can be 1,000 penalty units. A strict liability offence is one where proof of a fault element is not required and the defence of mistake of fact may be available.

The Magistrates Court (Nature Conservation Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005 (ACT) enables infringement notices to be issued and penalties applied for certain offences in the Nature Conservation Act. Infringement notices are intended to provide a quicker and more effective alternative to prosecution in court. The various offence provisions and penalties are prescribed in Schedule 1 to the regulation.

[5.5.4] Licences

Part 11 of the Nature Conservation Act enables the conservator to licence various activities which would otherwise be prohibited under the Act.

Under s.106 of the Act, the minister can determine criteria for granting or refusing a licence, imposing conditions on a licence, or determining the duration of a licence. No licence can be granted, or have conditions imposed or varied, except in accordance with these criteria. The current licensing criteria were issued as Nature Conservation (Licensing Criteria) Determination 2001 DI2001–47.

The Act also provides the minister with the power to determine fees (s.139). The current fees are prescribed under the Nature Conservation (Fees) Determination 2010 (No 1), DI2010–8.

Under the Nature Conservation Act, persons are required to hold a licence for keeping any parts of animals or whole animals, dead or alive, unless the animals are exempt, or being treated for illness, disease or injury, for up to 48 hours (s.46). Licences are renewable and can be of variable duration, as specified (s.107). A licence is not required to keep, possess, breed, buy, sell or dispose of species listed on the exempt list (ss.46-48). However, the animals must come from a legal source, and may not be taken, or come from the wild. Licensed keepers of animals must maintain prescribed records of any non-exempt animals, protected native animals, or special protection status animals (s.112), and produce them as required (s.113). Licence conditions can require private keepers to inform the licensing officer prior to importing or exporting any animal into or out of the ACT, and prior to selling, trading, or disposing of any animals in the ACT (including by donation). Penalties can be applied for non-compliance.

In the financial year 2007‑08 the conservator issued 634 'keep' licenses, permitting the private and commercial keeping of native animals including birds, reptiles, and amphibians and a small number of exotic species. Most of these were renewals. This figure included:

· 56 licences to import a native animal into the ACT

· 31 licences to export a native animal from the ACT

· 37 licences to take a native animal from the wild (for scientific research and later release)

· 121 new keep licences to keep a native animal during the reporting period

· four licences to remove and/or interfere with the nest of a native animal (related to authorised tree removal and relocation of the nest and animal).

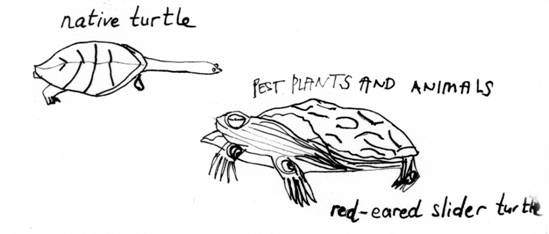

[5.5.5] Native Reptile Policy

The ACT Native Reptile Policy, which can be accessed from the TAMs website (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts), illustrates how these provisions work in practice. Native reptiles (lizards, snakes and turtles), whether alive or dead, may not be taken from the wild without a licence. The ACT has published a reptile policy to establish guidelines for assessing applications for licences and to regulate the keeping of reptiles. For hobbyists, no licence is required to hold exempt animals, which currently include captive-bred common Long-Necked Turtle (Chelodina longicollis), Eastern-Blue Tongue (Tiliqua scincoides), Blotched Blue-Tongue (Tiliqua nigrolutea), Shingleback Lizard (Trachydosaurus rugosus), and Bearded Dragon (Pogona barbatus). These are referred to as Category A species. Category B species, which currently consist of 18 species, are captive-bred species that may be held by experienced amateurs with at least two years experience in keeping one or more species from a family in Category A. Category C contains 28 species and is reserved for captive-bred reptiles suitable for keeping for hobby purposes for highly experienced herpetologists. Applicants must have at least one year's experience with keeping Category B species.

The policy allows licences to be granted to take non-venomous reptiles from the wild for scientific or educational purposes, and venomous reptiles to be taken from the wild for scientific purposes. When practicable these animals will be released at the capture site at the completion of the scientific study or educational exercise or surrendered to the service. Currently, suitably experienced members of the ACT Herpetological Association (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts) are permitted to take locally occurring non-venomous reptiles from the wild for the purpose of study at association meetings. As a condition of their licence, animals are released at the site of capture within 72 hours and records of take and release must be kept. There are rules governing the purchase and sale of animals, and the disposal of live and dead animals surrendered to the service.

Reptiles kept for scientific purposes must be kept at approved institutions, or if kept by private individuals at private residences, must be kept under a scientific project approved by the conservator. All reptiles must be kept in line with the institutions ethics committee's requirements and must not be in breach of any ACT legislation. The offspring of reptiles kept for scientific study cannot be disposed of without prior consent of the conservator.

Licences are rarely issued in relation to animals with special protection status, including migratory animals that are subject to a Commonwealth convention, treaty or agreement, and species vulnerable to or threatened with extinction. Under normal circumstances licences to keep reptiles belonging to this category will not be issued unless the conservator determines that the activity enhances the protection of the animal.

The deliberate cross-breeding (hybridisation) of captive reptile species and subspecies is not considered to be a desirable aim for the management of captive reptiles. In order to prevent possible genetic contamination of captive and wild populations, species or subspecies capable of hybridising must be housed separately.

[5.5.6] Land management agreements

The conservator has the power under the Nature Conservation Act to enter into a land management agreement with an agency (as defined). Under s.99, agency management agreements may deal with any or all of the following issues: access to land; fire management; drainage; management and maintenance of public or private facilities; rehabilitation of land or public or private facilities; indemnities; emergency procedures; internal stockpiling; fencing; feral animals and weed control.

In addition, under the Planning and Development Act 2007 (ACT), a rural lease will only be granted, renewed, varied or assigned if the person whose lease is renewed or varied, or the person to whom the lease is being assigned or granted, has entered into a management agreement with the ACT government, through the conservator (s.283).

Management agreements are important because they enable a landscape-scale approach to resource management to be adopted, embracing public lands and private lands such as rural leases. This is necessary because although the territory has an extensive amount of land that is protected, significant biodiversity, including remnant vegetation and important local habitat elements such as streams and hollow-bearing trees, are also found on rural leases and public land outside the reserve system.

In 2008 the TAMS said it would enhance its work with rural lessees to achieve landscape conservation connectivity. In 2008, most rural land management agreements, including those with conservation directions, were due or past their review days (which arises within five years of the date of signing). Due to prolonged drought and other factors, many rural landholders had not met their land management obligations, but TAMS said it would develop a strategic working relationship and facilitate access to funding to assist rural lessees to address environmental issues on their land.

[5.5.7] Conservation directions

Under Part 7 of the Nature Conservation Act, the conservator can give the occupier of land directions for the protection or conservation of native animals, plants and timber on the land. Directions must specify a time limit on compliance, and they must accord with any criteria in a disallowable instrument under s.62 of the Act.

The conservator can also direct the owner of a diseased native animal or plant to treat the animal or plant. Where the owner does not comply with the notice, or does, but the animal or plant does not respond satisfactorily, the conservator can require the animal or plant to be delivered up or destroyed. If the owner does not comply, a conservation officer may enter the land or premises where the animal is kept and seize it and then carry out treatment or dispose of or destroy the animal as he or she thinks fit.

Criteria for the issuance of directions were determined in 2001 in the Nature Conservation Criteria Determination DI2001–59. Penalties apply for failure to comply with a direction, without reasonable excuse. Issues have generally been managed through management agreements to date, or by negotiation.

[5.6] Wildlife in the suburbs

Residents have various responsibilities when native animals are in their suburb. For example, all snakes are protected under the Nature Conservation Act and cannot be killed unless they threaten life. Possums are also protected and cannot be trapped, killed or removed without a licence. The solution to possums living in the roof space is to block up any holes that allow them to get in, and then enjoy their antics outside. To assist the community to understand the importance of urban habitats and managing threats to that habitat, the Natural Heritage Trust and partner organisations supported the 2006 publication by ANUgreen of Life in the Suburbs: Urban Habitat Guidelines for the ACT.

One of the most significant threats to urban biodiversity is domestic pets. The Domestic Animals Act 2000 (ACT) provides for the identification and registration of certain animals and the duties of owners, carers and keepers. The Act provides for the registration of dogs, and the compulsory microchipping of declared dangerous dogs. A code of practice has also been approved by the Domestic Animals (Implanting Microchips in Dogs and Cats) Code of Practice 2008 (No 2) DI2008–73. Dogs over six months of age and cats over three months of age must be de-sexed unless a permit is issued otherwise. The aim of these provisions is to reduce the number of unwanted domestic pets, many of which the RSPCA euthanase each year, and to reduce predation of native wildlife in Canberra. Only four cats or dogs, with limited exceptions, can be owned without a multiple licence (s.18).

This Act also empowers the minister to declare a cat curfew (s.81) if cats in a particular area are a serious threat to native flora and fauna. The suburbs of Bonner, Forde, Mulligans Flat, and Goorooyarroo are Declared Cat Curfew Areas requiring 24-hour cat containment inside premises (see the Domestic Animals (Cat Curfew Area) Declaration 2004 (No 1) DI2004–201). Areas can also be designated as dog exercise and dog-on-leash areas (see Domestic Animals (Dog Control Areas) Declaration 2005 (No 1) DI2005–198).The Domestic Animals Act includes offence and penalty provisions. Infringement notices can be issued under the Magistrates Court Act 1930 (ACT) and the Magistrates Court (Domestic Animals Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005 SL2005–29.

[5.7] Pest plants and animals

As noted above, biodiversity in the ACT is threatened by pest plants and animals. Invasive species impact adversely on natural resources and agricultural activities. The Pest Plants and Animals Act 2005 (ACT) establishes a system for declaring plants and animals to be pests. Declarations may prescribe management actions and can require occupiers of premises to notify the appropriate authorities about the presence of a declared species.

Directions may be issued under Part 4 of the Act to the occupier of premises to eradicate or control pest plants or pest animals consistent with declared management plans. Contravention of a pest management direction is established as an offence carrying a penalty of up to 50 penalty units (s.27) and where a person has not undertaken something required by a direction, an authorised person may do so at the reasonable cost of the occupier (s.28).

The Act (Parts 2 and 3) also prohibits the propagation, importation and supply of certain pest plants or pest animals, or material contaminated with certain declared pest plants or pest animals. The Act establishes offences for activities, such as the use of vehicles and machinery contaminated with a prohibited pest plant or animal (ss.13 and 21) or the disposal of prohibited pest plants or animals or things contaminated with prohibited pest plants or animals, which would result, or be likely to result, in the spread of prohibited pest plants or pest animals (ss.15 and 24). Infringement notices can be issued under the Magistrates Court (Pest Plants and Animals Infringement Notices) Regulation 2005 (ACT) SL2005–34.

[5.8] Fisheries

The objects of the Fisheries Act 2000 (ACT) are to protect native fish species and their habitats, to provide high quality and viable recreational fishing, and to manage ACT fisheries sustainably. The Fisheries Act enables fishing closures (s.13) and other restrictions to be declared. The Fisheries Act provides four types of licence: commercial fishers; fish dealers; dealers in priority species; and an import/export licence (for live fish) (s.19). Under the Fisheries Act, there are restrictions on the number and size of fish that can be taken from public waters and it is an offence to disturb or damage spawn or spawning fish. To assist with sustainable fisheries management, under Part 2 of the Act, the conservator can prepare draft fisheries management plans on which he or she must invite written submissions before submitting the plan to the minister. The Act also includes offence and record-keeping provisions, authorises various conservation officers' powers, and provides for review of decisions.

[5.9] Review by the ACT Civil and Administrative Appeals Tribunal

Under the Nature Conservation Act and the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal Act 2008, the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal (ACAT) can review specified decisions made by the conservator. Under earlier legislation, see for example, Russell, George John and Conservator of Flora and Fauna (1996) ACTAAT 143 (20 May 1996). Reviewable decisions include those concerning directions, licences, refusals, prohibitions, restrictions and conditional approvals. For more details on actions in the ACAT, see [12.8.4] Tribunal review of a decision.

[5.10] Commonwealth legislation

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) is the most significant Commonwealth legislation relating to environmental protection, sustainable development and the conservation of biodiversity. The EPBC Act includes assessment and approval processes for certain actions, as well as provisions to protect biodiversity. It is not easy to separate these two aspects of the Act, as the former impacts significantly on the latter.

The actions that must be assessed and approved fall into two broad groups. The first group is actions carried out by the Commonwealth or its agencies, or those carried out on Commonwealth land or that will have an impact on Commonwealth land, and that are likely to have a significant impact on the environment. The second group is actions likely to have a significant impact on 'matters of national environmental significance'. Currently, those matters are:

· listed threatened species and communities

· listed migratory species

· Ramsar wetlands of international importance

· the Commonwealth marine environment

· World Heritage properties

· National Heritage places

· nuclear actions.

As the ACT has many Commonwealth agencies and much Commonwealth land, as well as a Ramsar wetland at Ginini Flats in Namadgi National Park, numerous migratory species and listed threated species and communities, the EPBC Act is important law applicable in the territory. ACT Environmental Law Handbook Chapter 4 describes the referral and assessment processes of the EPBC Act (at [4.5.6] Referral process, [4.5.7] Environmental impact assessment process and [4.5.8] Bilateral agreements and accredited assessment). The EPBC Act also provides for the:

· identification and monitoring of biodiversity and making of bioregional plans

· identification and listing of threatened species and threatened ecological communities and key threatening processes

· development of recovery plans, threat abatement plans and wildlife conservation plans

· regulation of trade in wildlife and access to prescribed genetic resources

· administration of a Register of Critical Habitat

· compliance and enforcement of the Act.

The EPBC Act lists threatened species under six categories: extinct, extinct in the wild, critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable and conservation dependent. There are three categories of threatened ecological communities: critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable.

At the time of writing there were 17 listed key threatening processes under the EPBC Act, including: land clearance; dieback; competition and land degradation by feral goats and rabbits; predation by feral cats and the European red fox; predation, habitat destruction, competition and disease transmission by feral pigs; and the loss of climatic habitat caused by anthropocentric emissions of greenhouse gases.

Any person may nominate a native species, ecological community or threatening process for listing under any of the categories specified in the EPBC Act.

Nominations, except those that are vexatious, frivolous or not made in good faith, are forwarded by the Commonwealth minister to the Threatened Species Scientific Committee. The Committee prepares a priority assessment list for the Minister who finalises the list. The committee then consults with stakeholders on the finalised priority assessment list, and assesses each nomination against the relevant criteria. Once the threatened species committee has completed the assessment, its advice is forwarded to the Commonwealth minister who makes the final decision. If the minister accepts the recommendation, then the species, community or process is added to the lists under the EPBC Act.

Recovery plans made, adopted or implemented under the Act set out what must be done to protect and restore important populations of threatened species and communities, as well as how to manage and reduce threatening processes. Before making or adopting a recovery plan the Commonwealth minister must:

· consult with relevant state and territory ministers where the species or community occurs

· consider advice from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee

· invite public comment

· consider all comments received.

Various species listed as vulnerable or endangered under the ACT's Nature Conservation Act also have recovery plans for them under the EPBC Act, including the Regent Honeyeater (Xanthomyza Phrygia), Striped Legless Lizard (Delma impar), Trout Cod (Maccullochella macquariensis) and Tuggeranong Lignum (Muehlenbeckia Tuggeranong).

If a habitat is identified in a recovery plan as critical to the survival of a species or community, then the minister must consider whether to list that habitat on the Register of Critical Habitat. Damaging critical habitat in a Commonwealth area is punishable by a fine of up to 1,000 penalty units (currently $110,000) or imprisonment for two years, or both (s.207B).

Threat abatement plans cover the research and management actions that need to be taken to reduce the impact of a listed key threatening process. Within 90 days of listing a process, the Commonwealth minister must decide whether an abatement plan is a feasible, effective and efficient way to abate the process. If a plan is to be developed, that fact must be advertised and comment invited. At the time of writing ten plans had been approved, including those relating to beak and feather disease affecting endangered parrots (Psittacine species), infection of amphibians with chytrid fungus resulting in chytridiomycosis, sea bird by-catch during long line fishing, dieback caused by the root-rot fungus Phytophthora cinnamomi, the activities of feral cats, pigs, rabbits, goats, and foxes, and reduction in impacts of tramp ants on biodiversity in Australia and its territories

Other protective tools under the EPBC Act are legally binding conservation agreements between the Commonwealth minister and another person for the protection and conservation of biodiversity (Part 14). These can require, among other things, that a person carry out certain activities, refrain from carrying out activities, or spend granted money in a certain way.

The Commonwealth minister may also make conservation orders to protect listed threatened species or communities, requiring or prohibiting certain actions in Commonwealth areas (Div.13 of Part 17). Contravention of a conservation order is an offence.

Permits are required under the Act for certain activities, including whale watching in Commonwealth waters, research or commercial activities in Commonwealth parks or reserves, and activities in Commonwealth areas that may affect listed species or communities. It is an offence to kill, injure, take, trade, keep or move a member of a listed species or community in a Commonwealth area without a permit (Div.1, Part 13 of Chapter 5).

For up-to-date information consult the Department of Environment, Heritage and Arts website which includes extensive material on the operation of the EPBC Act (see ACT Environmental Law Handbook Contacts).

[5.10.1] National policy development

National policy development is also underway aimed at improving biodiversity conservation outcomes. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) and the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council (NRMMC) have both identified biodiversity as a priority for climate change adaptation. In 2004 the NRMMC released the National Biodiversity and Climate Change Action Plan, which sets out a series of adaptation strategies and actions to minimise the impacts of climate change on biodiversity by maximising the capacity of species and ecosystems to adapt to future climates.

In 2008 the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts was developing a National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Biodiversity, to update the earlier 1996 Strategy. The strategy implements Australia's obligations under the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity in a policy sense, as does legislation.

The National Framework for the Management and Monitoring of Australia's Native Vegetation (2001) is also being reviewed. In April 2008 the NRMMC agreed that the Natural Resource Management Standing Committee would finalise the review of the framework, taking account of the review of the Biodiversity Strategy, and report to Council in 2009. A draft revised Native Vegetation Framework is currently scheduled to be released for public consultation from February to March 2010.

The Commonwealth and each state and territory are also entering into bilateral agreements for the assessment of the future impacts of land use change on matters including biodiversity under the EPBC Act. Under strategic assessments, development proposals are assessed through a combined assessment process covering both Commonwealth and state responsibilities. These are regional-scale assessments which aim to reduce duplication by assessing classes of development, and which avoid the need for separate Commonwealth and state or territory assessments and approvals. COAG instructed the Business Regulation and Competition Working Group (BRCWG) to report back to COAG at its October 2008 meeting with a framework for identifying opportunities for strategic assessments.

Most jurisdictions have already concluded other bilateral agreements under the EPBC Act (s.45) to streamline environmental impact assessments and reduce duplication between Commonwealth and state and territory jurisdictions. The bilateral environmental impact assessment agreement for the ACT under the EPBC Act was finalised on 4 June 2009.

[5.11] Conclusion

This chapter has provided an introduction to the legislative provisions framing some interactions with biodiversity in the ACT. Natural resource management, including biodiversity conservation, ranges from broad scale regional planning and management, to the micro management of licences. The trend in law and policy is away from species-specific approaches to a more integrated and holistic planning and management approach that partially relies on conservation and sustainable development partnerships with community stakeholders for its success. An overarching objective in this approach is to ensure that sufficient habitat is available for species to ensure their survival. Dramatic and ambitious examples of the policy trend to bioregional and even continental scale land use planning and connectivity include the Australian Bush Heritage's 'Kosciuzsko to Coast' project, and 'the Great Eastern Ranges Initiative' wildlife corridor proposal. Connectivity is already recognised in numerous ACT policy documents, including the action plans adopted under the Nature Conservation Act. The proposal to nominate the ACT as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve also includes broad-scale sustainability objectives, but if it progresses, it will most likely be without legislative underpinnings.

Governments, industry, community groups, rural lessees and individuals can all contribute to protecting, restoring, monitoring and evaluating biodiversity in the ACT. Planning law and policy, and governments' inter-governmental regional natural resource management framework, and the projects that are funded and implemented in partnership with community investment, are particularly important. The community's voluntary contributions through activities with Greening Australia, Park care, Landcare, Waterwatch and 'Friends of…' are also important. But so is living sustainably, advocating for sustainability during participatory policy development, and by using territory and Commonwealth legislation to protect biodiversity in the territory and region.

[5.12] Table: Uncommon, vulnerable and endangered species and ecological communities protected in the ACT1, NSW2 and the Commonwealth3.

KEY: AP = Action Plan, as numbered Nature Conservation Act 1980 (ACT)

Cth = Australian Government jurisdiction

UC = uncommon or of conservation concern, as referred to in action plans

V = vulnerable

E = endangered

CE = critically endangered

SPS = Special Protection Status in ACT. The list below does not a number of Schedule 5, Migratory Animal Wildlife species, such as Rainbow Bee-eater, which may visit the ACT.

[5.12.1] Native plants

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Canberra Spider Orchid |

Arachnorchis actensis |

E, SPS |

CE |

- |

- |

|

Mauve Burr-daisy[i] |

Calotis glandulosa |

- |

V |

V |

AP28 |

|

Brindabella Midge Orchid |

Corunastylis ectopa |

E, SPS |

CE |

- |

|

|

Emu-foot |

Cullen tenax |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Australian Anchor Plant |

Discaria pubescens |

UC |

- |

- |

AP27/9 |

|

Michelago Parrot-pea9 |

Dillwynia glaucula |

- |

- |

E |

AP28 |

|

Wedge Diuris |

Diuris dendrobioides |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Golden Moths |

Diuris pedunculata |

UC |

E |

E |

AP28 |

|

Purple Diuris |

Diuris punctata var. punctata |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Creeping Hopbush9 |

Dodonaea procumbens |

- |

V |

V |

AP28 |

|

Mountain Cress |

Drabastrum alpestre |

UC |

- |

- |

AP29 |

|

a subalpine herb |

Gentiana baeuerlenii |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP5 |

|

Yam Daisy |

Microseris lanceolata |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Ginniderra Peppercress |

Lepidium ginninderrense |

E, SPS |

V |

- |

AP28 |

|

Hairy Buttons |

Leptorhynchos elongates |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Hoary Sunray (white form) |

Leucochrysum albicans var. tricolour |

UC |

E |

- |

AP27 |

|

Austral Trefoil |

Lotus australis |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Tuggeranong Lignum |

Muehlenbeckia tuggeranong |

E, SPS |

E |

- |

AP29 |

|

a milkwort |

Polygala japonica |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

a leek orchid (sometimes known as Tarengo Leek Orchid) |

Prasophyllum petilum |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP27/8 |

|

no common name |

Pomaderris pallida |

UC |

V |

V |

AP29 |

|

Monaro Golden Daisy9 |

Rutidosis leiolepis |

- |

V |

V |

AP28 |

|

Button Wrinklewort |

Rutidosis leptorhynchoides |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP28 |

|

Wild Shorgum |

Sorghum leiocladum |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Mountain Swainson-pea |

Swainsona monticola |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

|

Small Purple Pea |

Swainsona recta |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP27 |

|

Silky Swainson-pea |

Swainsona sericea |

UC |

- |

V |

AP27/8 |

|

Austral Toadflax |

Thesium australe |

UC |

V |

V |

AP27/8/9 |

|

Zornia |

Zornia dictiocarpia |

UC |

|

|

AP27 |

[5.12.2] Native birds

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Gang-Gang Cockatoo |

Callocephalon fimbriatum |

- |

- |

E4 & V |

- |

|

Brown Treecreeper |

Climacteris picumnus |

V |

- |

V |

AP27 |

|

Varied Sitella |

Daphoenositta chrysoptera |

V |

- |

- |

AP27 |

|

Diamond Firetail |

Emblema guttatum |

- |

- |

V |

AP27 |

|

Crested Shrike-tit |

Falcunculus frontatus |

- |

- |

- |

AP27 |

|

Painted Honeyeater |

Grantiella picta |

V |

- |

V |

AP27/9 |

|

Little Eagle |

Hieraaetus morphnoides |

V |

|

|

|

|

White-winged Triller |

Lalage sueurii |

V |

- |

- |

AP27 |

|

Swift Parrot |

Lathamus discolor |

V, SPS |

E |

E |

AP27 |

|

Hooded Robin |

Melanodryas cucullata |

V |

- |

V |

AP27 |

|

Barking Owl |

Ninox connivens |

- |

- |

V |

AP27 |

|

Flame Robin |

Petroica phoenicea |

- |

- |

- |

AP27 |

|

Superb Parrot |

Polytelis swainsonii |

V |

V |

V |

AP27 |

|

Speckled Warbler |

Sericornis sagittatus |

- |

- |

V |

AP27 |

|

Regent Honeyeater |

Xanthomyza Phrygia |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP27 |

[5.12.3] Native mammals

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Spotted-tailed Quoll |

Dasyurus maculatus |

V |

E |

V |

AP30 |

|

Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby |

Petrogale penicillata |

E, SPS |

V |

E |

AP22 |

|

Smoky Mouse |

Pseudomys fumeus |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP23 |

|

Squirrel Glider |

Petaurus norfolcensis |

- |

- |

E5 & V |

AP27 |

|

Koala |

Phascolarctos cinereus |

- |

- |

E6 & V |

AP27 |

[5.12.4] Native reptiles

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Pink-tailed Worm Lizard |

Aprasia parapulchella |

V, SPS |

V |

V |

AP29 |

|

Striped Legless Lizard |

Delma impar |

V |

V |

V |

AP28 |

|

Grassland Earless Dragon |

Tympanocryptis pinguicolla |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP28 |

|

Rosenberg's Monitor |

Varanus rosenbergi |

- |

|

V |

AP27 |

[5.12.5] Native frog

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Northern Corroboree Frog |

Pseudophryne pengilleyi |

E, SPS |

V |

V |

AP6 |

[5.12.6] Native fish and crustaceans

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Silver Perch |

Bidyanus bidyanus |

E, SPS |

- |

V |

AP29 |

|

Two-spined Blackfish |

Gadopsis bispinosus |

V |

- |

- |

AP29 |

|

Trout Cod |

Maccullochella macquariensis |

E, SPS |

E |

E |

AP29 |

|

Murray Cod |

Maccullochella peelii peelii |

- |

- |

- |

AP29 |

|

Macquarie Perch |

Macquaria australasica |

E, SPS |

E |

V |

AP29 |

|

Murray River Crayfish |

Euastacus armatus |

V |

- |

- |

AP29 |

[5.12.7] Native invertebrates

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Perunga Grasshopper |

Perunga ochracea |

V |

- |

- |

AP28 |

|

Golden Sun Moth |

Synemon plana |

E, SPS |

CE |

E |

AP28 |

[5.12.8] Ecological community

|

Common name |

Scientific name |

ACT |

Cth |

NSW |

AP |

|

Natural Temperate Grassland |

|

E |

E8 |

- |

AP28 |

|

Yellow Box/Red Gum Grassy Woodland |

|

E |

CE9 |

E10 |

AP27 |

1 Nature Conservation (Species and Ecological Communities) Declaration 2008 (No 2)DI2008–53; Nature Conservation (Special Protection Status) Declaration 2005 (No 1)DI2005-64

2 Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW); Fisheries Management Act 1994 (NSW)

3 EPBC Act List of Threatened Flora www.environment.gov.au/; EPBC Act List of Threatened Fauna www.environment.gov.au/

4 Species in ACT region but not known in ACT

5 Gang-gang Cockatoo population in the Hornsby and Ku-ring-gai Local Government Areas

6 Squirrel Glider on Barrenjoey Peninsula, north of Bushrangers Hill

7 Koala, Hawks Nest and Tea Gardens population; Koala in the Pittwater Local Government Area

8 White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely's Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland

9 White Box Yellow Box Blakely’s Red Gum Woodland (as described in the final determination of the Scientific Committee to list the ecological community)

10 Species in ACT region but not known in ACT